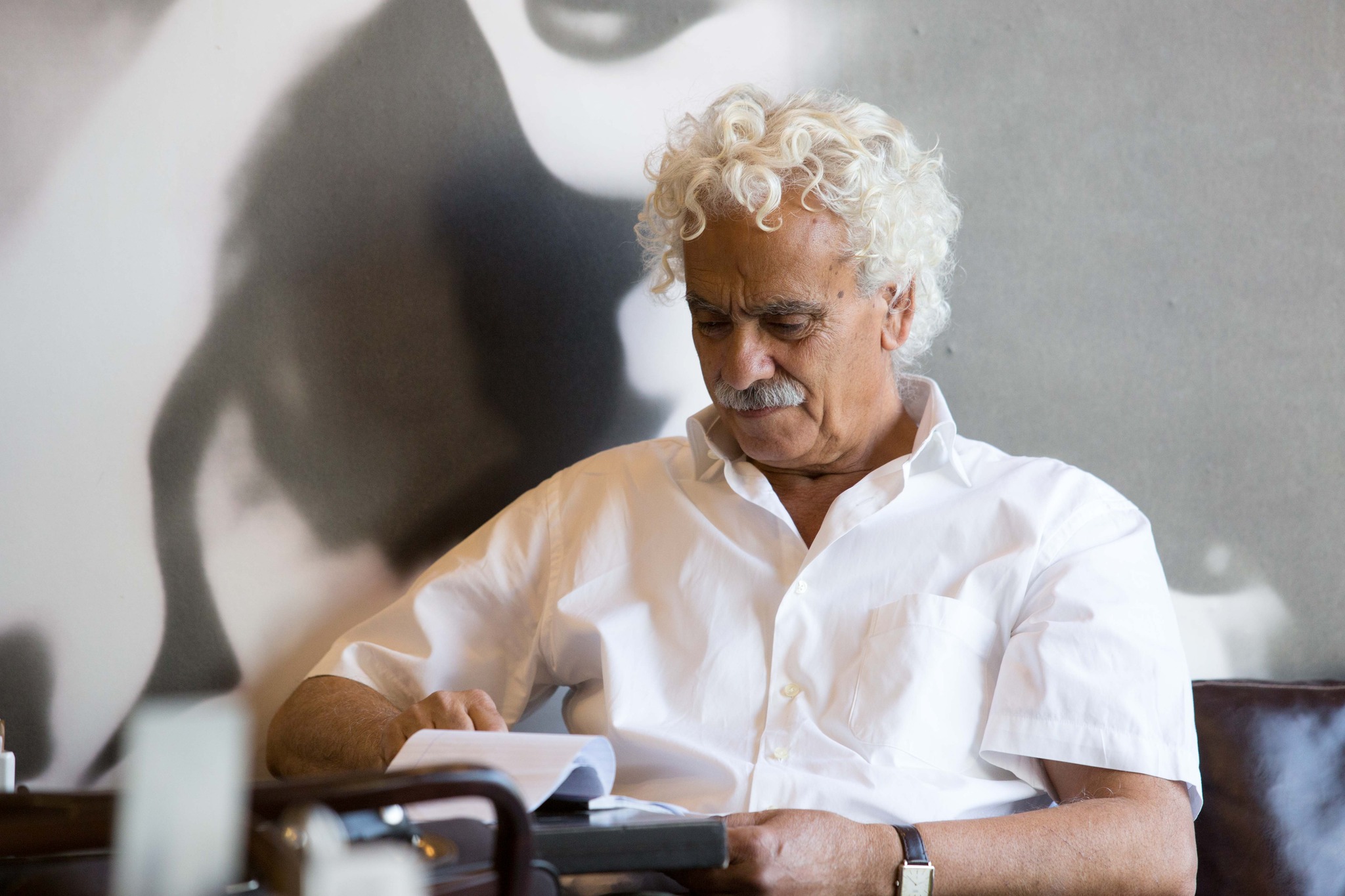

For So J. Lee, 2020 has been a year of growth. Just two years after their first translations were published, the Seoul-based writer and translator became Modern Poetry in Translation’s current Writer-in-Residence, recently released the fourth issue of chogwa (their quarterly e-zine showcasing multiple translations of a single poem), and will publish their full-length translation of Lee Hyemi’s Unexpected Vanilla next month, followed by Choi Jin-young’s To the Warm Horizon and Lee Soho’s Catcalling in 2021.

For an emerging translator working in the midst of a global pandemic, Lee’s list of publications is undeniably impressive. But one of the many things that 2020 seems intent on teaching us is that growth can no longer be measured solely in terms of productivity and output. In correspondence and conversation, it’s clear that So J. Lee has already embraced a new kind of metric, acknowledging growing pains and citing introspections, laughter, and everyday pleasures as equally significant indicators of their progression. This was especially evident when I contacted Lee in June, keen to learn more about their forthcoming books, zine, bilingual events, and drag performance. I wanted to begin our interview with a discussion around the imminent publication of Unexpected Vanilla, but instead, Lee asked if we could start the conversation with an unusual announcement . . .

—Sarah Timmer Harvey, July 2020

So J. Lee (SJL): Can I start this interview by announcing my hibernation this winter?

Sarah Timmer Harvey (STH): Of course! Can I ask why you intend to hibernate?

SJL: When Kim Tae-ri was asked about her plans after shooting a film and a TV series back-to-back in 2018, she said, “I plan to enter hibernation. I grew ten cm over the winter break prior starting high school. Let’s see what happens this time.” I love her casual re-articulation of rest as an opportunity for growth. I mean, rest is also rest. I don’t want to glamorize busyness, in the slim chance anyone sees me as a glamorous being. My vibe is more Pizza Rat anyway.

STH: Apart from the obvious pressures facing the world at the moment, what has kept you from resting over the past few months?

SJL: Grief. Ineffable grief and rage. Somehow we have to rest and allow for joy amidst it all. I’m still practicing.

I’m animated by my three forthcoming books, Lee Hyemi’s Unexpected Vanilla, Choi Jin-young’s To the Warm Horizon (Honford Star, 2021), and Lee Soho’s Catcalling (Open Letter Books, 2021), all of which I reflect on in my recent essay, “Not Exactly a Sister.” I translate women writers who write about women for women, so the word Unni became an organic through-line for introducing their works all at once.

As Modern Poetry in Translation’s Writer-in-Residence, I’m also hosting a virtual workshop on Lee Jenny’s concrete poem “Space Boy Wearing a Skirt.” After that will be my interview with Lee Soho and the fifth issue of chogwa!

STH: Wow, you have been busy! Can we talk about your translation of Lee Hyemi’s Unexpected Vanilla, which is set to be published by Tilted Axis next month? In 2019, Asymptote published several poems from the collection, including my favourite, “Erasable Seeds.” The poem describes a connection between two people as “a newly thickening forest” grown from “small seeds.” I think about that poem a lot. Like most of Lee Hyemi’s work, it is incredibly sensual and also reminds me of that moment when you first read a poem or line in someone’s poetry or fiction that’s so striking, you know that you just have to translate it. Do you remember which line of Unexpected Vanilla did that for you?

SJL: I was assigned in a translation workshop to translate a poet I’d never read before, and I wanted to try someone younger than Heo Su-gyeong, whose poems I’d tried translating as an undergrad. Then a title caught my eye: Unexpected Vanilla. I read the poem “Femdom” in the final section and realized that this young Korean woman was writing surrealistically about kink! I wanted to tell all my friends about it, which remains my biggest motivation to translate.

I’ve written about the Unni line in “Cupboard with Strawberry Jam” so many times already, but it’s simply iconic. Plus, Lee Hyemi wrote a variation of that line in my copy of the book: “We must be one person, cunningly divergent. Sharing an intimate language.” I’ll always remember the way she pulled out a stamp shaped like a fish and blended multiple colors before pressing it to the page. READ MORE…