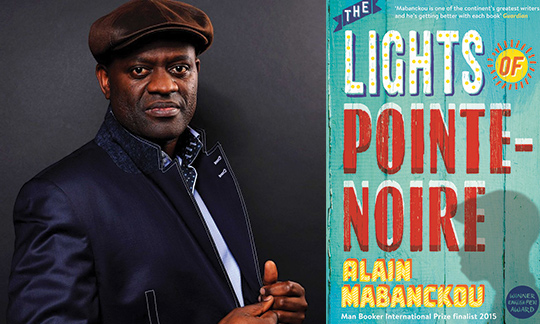

Last Translation Tuesday, we brought you the nonfiction winner of our annual Close Approximations translation contest, picked by Margaret Jull Costa. This week, we present the fiction winner: Ruth Diver’s translation from the French of Sophie Pujas’s fiction, which marks the first time her work has been published in English. Judge Ottilie Mulzet, an award-winning translator herself who has translated László Krasznahorkai’s fiction, chose Diver’s entry because it “combines excitingly experimental writing in a wonderful translation. To me the English version reads perfectly, truly attaining that marvellous balance where, as readers, we are well aware of being privy to a textual world otherwise not available to the Anglophone reader: Diver steers well clear of over-domesticization, and yet at the same time, her translation never contains the infelicity of a clumsy rendering. The author’s voice—a combination of lucidity and ironic sympathy for her anonymous characters intersecting with the urban geography of Paris—is captured magnificently. I truly hope this work will find a home with a book publisher.“

—The editors at Asymptote

***

AUTUMN

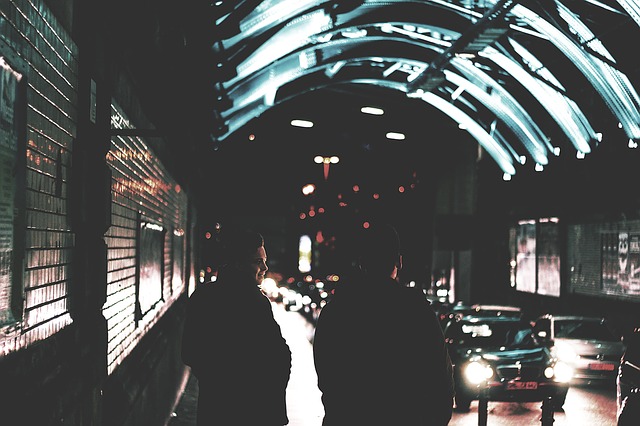

Rue de l’Odéon (6th)

Life rushes around him, but he’s not involved. The city rumbles comfortably, but he doesn’t belong. Homeless? What a joke. He’s already been here eight years. On the same ventilation grille. Staring at the window of the same café. The passersby grow old and die. He is eternal, stuck under a trapdoor in time. The devotion of those who wanted to help him has worn out. Nobody can imagine any other life for him now. He doesn’t care. He knew it could never happen.

Sometimes he throws insults randomly about. It’s relaxing, this sudden emptiness around him.

He carefully avoids seeing himself. A beard and long hair, just to be on the safe side. Even if he had a face, there’s no chance he will ever see it again. READ MORE…