The action of the novel takes place in one day (as in Joyce’s Ulysses and Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway). The main character is Simon Blef, a man who has emigrated to Holland, where he met his future wife, a Mexican-Dutch girl named Estrella. As he waits for Estrella, who is returning from Spain, Simon wanders into the Amsterdam pubs and starts drinking. As time passes, all kinds of memories surface from the past. There is no striking action in the novel; it is rather an impressionistic reverie with glimpses of humour and a mordant commentary on the main character’s ambition to become a writer. This novel was shortlisted for Slovakia’s most prestigious literary award, Anasoft Litera Prize, in 2011.

***

1. There’s somebody

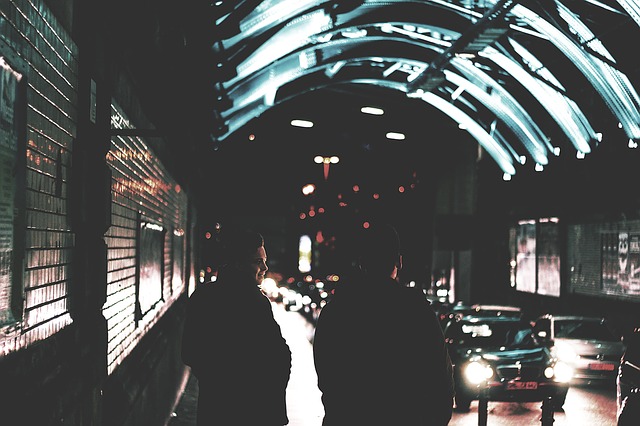

whose refuge is a pub like this, neither filthy nor speckless, but the sort of place where a passer-by does not stay too long. Battered, creaky chairs, dust-coated wooden panelling, a slot machine. For somebody refuge means a bar counter, subdued conversation, light music, world-famous glances from bronzed faces. For someone, again, it’s a woman willing to hear the cycled effusions of pain, morning and evening. Hear them, care for them, cultivate and protect them. Fantasies of alleged wrongs and menaces. For Simon Blef, whom no misery is tormenting today and therefore he claims no concern, refuge means this Amsterdam pub, neither filthy nor speckless, scrunched at the corner of Gravensstraat and Nieuwe Zijdsvoorburgwal. From there Simon Blef gazes at the world, observes passers-by, how they borrow and steal gestures, each in a way that is both unique and custom-worn. Not quite half an hour ago he was boring through the crowds that came hurtling out from the platforms of Centraal Station and wondering whether to go left and find some quiet boozer in the Red Light District sidestreets, or if he ought to go right and cast anchor as ever in this unprepossessing drinking shop, which basically serves as an entrance hall for a hotel and restaurant on the first floor.

Simon has picked his spot by the window so as to be able to see the doings not only on the street but also by the bar counter. Encompassing with one’s gaze the largest possible segment of the world currently served up: then he feels in a place of refuge. READ MORE…