When we first started the What’s New in Translation column in 2015, it was to offer readers a look at the incredible work done by writers, translators, and publishers all around the world. Gathering some of the most exciting publications coming out each month, the column featured regular reviews from trusted critical voices, giving the spotlight over to this great wealth of literary work. A lot has changed in the last decade; though English still reigns, we’ve seen the advocates of literary translation win a lot of battles as they seek to make our reading landscape a more various, inclusive, and interconnected space. As such, we now feel the need to extend our purview to include more of these brilliant voices, more of this innovative work, more of the insights and wonders that they bring. We are delighted to announce that our monthly column will now feature a greater number of titles —but with the same incisive critical insight that we’ve always aimed to bring.

From Argentinian horror to the latest from a Hungarian master of form, an intergenerational Greek tale to haiku interpretations, read below for a list of the ten most exciting books out in September.

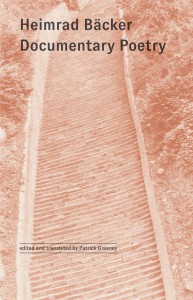

Documentary Poetry by Heimrad Bäcker, translated from the German by Patrick Greaney, Winter Editions, 2024

Review by Fani Avramopoulou

Documentary Poetry compiles a selection of German poet Heimrad Bäcker’s documentary poems and photographs with his published interviews, lectures, and essays, offering a richly contextualized introduction to his many decades of work documenting and reflecting on the Holocaust. Bäcker does not conceal his relation to the Nazi Party; he was an avid member for about a year, joining at the age of eighteen. He then denounced the Nazi ideology in the wake of the Nuremberg trials, and spent the rest of his life meticulously chronicling the Third Reich’s atrocities through photography and a poetic method he described as his “transcript system.” The collection’s title essay introduces what feels like the conceptual seed of Bäcker’s work: a reflection on the Nazis’ use of ordinary language to conceal, sanitize, enable, and systematize the horrors of the Holocaust. His conceptualization of language as a participatory, covert administrative tool of the Nazi ideological agenda leads to this development of the transcript system as a form of intervention—a way of undressing such language and purging it of its duplicities.