In this month’s round-up of the latest in world literature, our editors bring vital texts addressing faith, (false) mythologies, desire, migration, and Indigenous culture to the forefront: a collection of penetrating, prismatic poems from the lauded Egyptian poet Iman Mersal; from South Korea’s Lee Geum-yi, a fiction that tells the long-silenced stories of women crossing the seas to be wed to strangers; and a new collection of poetry, documenting Ojibwe lives, by eminent writer Linda LeGarde Grover. Read on to find out more!

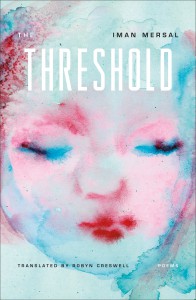

The Threshold by Iman Mersal, translated from the Arabic by Robyn Creswell, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022

Review by Alex Tan, Senior Assistant Editor

Perhaps it begins with a search. The Egyptian poet Iman Mersal returns to her homeland in hopes of procuring a book by Saniya Saleh, an elusive writer no one seems to have heard of. Instead she finds a table, piled with the canonized words of men; nowhere in sight is the person she seeks: a wife, sister, and mother, who can only secondarily be a writer in her own right. “I don’t know how she likes to see herself,” she laments in a wandering essay. Left with the “wasted potential” of what survives, she can imagine only a voice of muted cadence, “a whispered song of mourning which slips through to me amid the din of revolutionaries’ rabble-rousing slogans, of warriors intent on victory, of those broken by defeat angrily denouncing state, dictator and society.”

A similar quality of whispering, of slipping through, inhabits Iman Mersal’s angular The Threshold, a collection of poetry translated delicately by Robyn Creswell in conversation with the poet herself. In the titular piece, a collective biography of sorts charts a path through the streets and labyrinthine hypocrisies of Cairo in the nineties: “one long-serving intellectual screamed at his friend / When I’m talking about democracy / you shut the hell up.” Elsewhere a speaker ventures, “Let’s assume the people isn’t a dirty word and that we know the meaning of en masse.” Yet this momentary compact reveals its own fragility; language with all its alibis and forms of subterfuge seems a poor vessel, too riddled with holes to hold “all the wasted days” and the “nights / of walking with hands stretched out / and the visions that crept over the walls.”

Mersal’s work is unafraid of its own promontories and edges. Often, the writing advances a crepuscular view of the self, ever-partial and shrouded in semi-obscurity, divided from its figurations. The opening poem dryly declares, “I’m pretty sure / my self-exposures / are for me to hide behind.” Her name, which contains the Arabic for “faith” and “messenger,” is too “musical” for “a body like my body / and lungs like these—growing raspier / by the day.” On what map might we locate the trembling contours of that occluded life, “whose existence I’ve never been sure of,” and which appears to “have neither past nor future” in an encounter with a stranger, on whose shoulder she accidentally falls asleep? How unwieldy it feels in its bulk, how relentlessly it has been anatomized, in spite of its wispy resistance to measurement:

This is the life into which more than one father stuffed his ambitions, more than one mother her scissors, more than one doctor his pills, more than one activist his sword, more than one institution its stupidity, and more than one school of poetry its poetics.