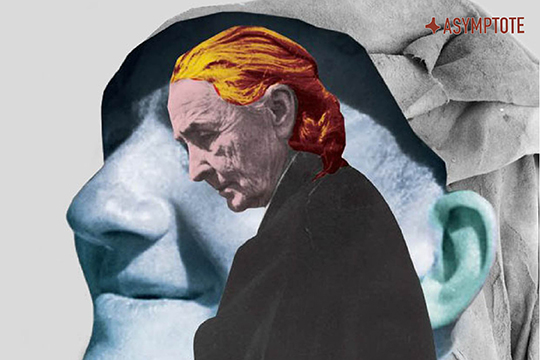

Mexican author Cristina Rivera Garza is a foremost voice in contemporary Mexican literature. Known for her frequently dark subject matter and hybrid styles, her work focuses on marginalized people, challenging us to reconsider our preconceptions about boundaries and transgression. She has won major literary awards and is the only author to have twice won the International Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz Award (in 2011 and 2009). Her latest work to be translated into English, Grieving: Dispatches from a Wounded Country, has just been published by Feminist Press and is a hybrid collection of journalism, crónicas, and essays, that explore systemic violence in contemporary Mexico and along the US-Mexico border. To coincide with its much-anticipated release, Asymptote’s Assistant Managing Editor Lindsay Semel spoke with Cristina Rivera Garza about the ideas behind this compelling work.

“Let me just bring some tea, and I’ll be right back!” Cristina Rivera Garza dashed out of her Zoom screen briefly before settling back into her chair and adjusting her glasses with a warm smile, her air of familiarity challenging the oppressiveness of the geographical and technological distance to which we’ve lately become accustomed. In the following interview, we discuss Grieving: Dispatches from a Wounded Country, the striking latest collaboration between Garza and translator Sarah Booker. She reflects upon the demands that she makes of syntax, the enigmatic character of reality, the importance of solidarity and imagination, and how she and Booker coined the term “The Visceraless State.” Very much of the borderland between Mexico and the United States, her work meets the global, contemporary moment not despite its specificity, but because of it.

—Lindsay Semel, Assistant Managing Editor

Lindsay Semel (LS): You’ve stated in interviews, and it’s apparent in your work, that you intentionally test the limits between what language normally does and what it can do in order to discover new experiential possibilities between writer, text, and reader. I wonder if you could point to places in the text where you tested and stretched the limits of Spanish but were not able to do so the same way in English and vice versa. How do Spanish and English need to be challenged differently?

Cristina Rivera Garza (CRG): Every single project has to challenge language in specific ways. It always depends on the materials that I’m exploring, affecting, and letting myself be affected by, and there are specific ways that you can do that both in English and in Spanish. I tend to write longer sentences in Spanish and more fragmentarily in English, for example. When I am getting too long-winded in Spanish, I try to convey that thought with the directness and economy I associate with my relationship with English. At times, I try to use the semicolon in English, just because it is more common in Spanish and I want to see what happens to both sentence and sense. Constantly borrowing from English and borrowing from Spanish and taking traces and echoes from one language into the other, trying to honor and replicate the tension and friction that maintains them together where I live and how I think, has been almost a natural way of continuing to challenge both.

Sarah [Booker, translator of Grieving] is such a deft translator and we now know each other quite well. She’s been translating my work for a number of years and we have a very open, fluid conversation as she goes into the translation process: less a process of moving language from one context to a another, and more a search for similar effects based on the affective capacities of host and receiving languages. I work closely with syntax, especially if I’m exploring issues such as violence and suffering. Pause, breathlessness, all those aspects of a body going through tremendous pressure or pain inflicted—in terms of keeping both form and content responding to the same challenges, it is important that syntax and semantics are somehow reflecting and embodying that experience. That’s when writing occurs.

I think of translation as a creative process too. I see Sarah as my co-author and her work as a way through which I receive my book back anew. I think she’s a poet at heart. I don’t know if she knows that, but all those experiments with language, that’s something she’s very deft at. READ MORE…