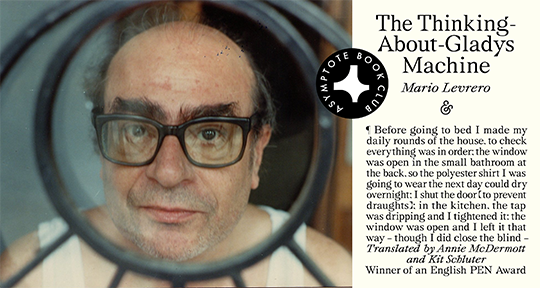

The world is strange, and we make it stranger by living here. Uruguayan author Mario Levrero knew that better than most, and in his debut collection of short stories, The Thinking-About-Gladys Machine, one is guided by extraordinary vision and delightful humour along the writer’s gallery of fantasies and absurdities, impossible events and otherworldly journeys, all of which are made real and cemented into reality by thought and emotion. In this interview, translator Annie McDermott speaks about being drawn into Levrero’s singular voice, working with co-translator Kit Schluter, and distinguishing imagination from invention.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Georgina Fooks (GF): How did you first encounter Mario Levrero’s work, and what drew you to his writing?

Annie McDermott (AD): It was through a series of strange coincidences—which seems fitting. I was living in Brazil at the time, and I happened to go for lunch with a Mexican writer called Juan Pablo Villalobos, who was also living in Brazil at the time, and he is a great fan of Levrero. He wrote a great piece for Granta about how he became a fan before he’d even had the chance to get his hands on any of Levrero’s books—because they used to be so hard to get hold of—and he became a fan based on the titles alone.

He recommended him to me, and I happened to be going to Uruguay on the way home from Brazil, and I picked up a copy of one of Levrero’s novels. I remember that as soon as I started reading it, I realised that I’ve never read anything else like it. He has this amazing voice, this kind of strange, absurd, quite deadpan voice that is like nothing else. It’s also very warm, and also really engaging, and also very companionable and a really pleasant narrator to spend time with.

At the same time, Juan Pablo Villalobos had also been enthusiastically recommending Levrero to Stefan [Tobler] from And Other Stories, so it all happened in parallel in a very pleasing way, and that was how I came to end up doing some samples and eventually translating Levrero’s books. READ MORE…