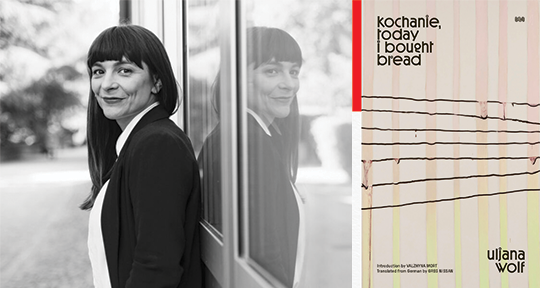

kochanie, today i bought bread by Uljana Wolf, translated from the German by Greg Nissan, World Poetry Books, 2023

In German, Uljana Wolf’s work inhabits the liminal spaces between the German and Polish languages, with all the fraught history that this double heritage involves. Now, in an English translation by Greg Nissan, this palimpsest of linguistic plurality has received another layer. Born in the German/Polish borderlands, Wolf has rapidly become a voice for a globalised, post-GDR generation, her life and work echoing the political and social upheaval of the twentieth century. In compact scenes of personal and shared experience, both dreamlike and jarring, she weaves together metaphoric word-sounds, juxtaposed imagery, and multilingualism. Nissan’s expert translations, in turn, are contemporary in the sense that they are unapologetically “unfaithful”. He has incorporated new imagery into the retold poems, such as the echoes of mink fur in “mornmink”, reiterating that his translated poems should not be seen as reproductions or ‘shadows’ of the original, but rather as a “jealous lover, eager to retort”.

Wolf’s verse is extremely dense and laden with historical and cultural references, making both the foreword by Valzhyna Mort and the afterword by Greg Nissan crucial pieces of the puzzle in beginning to decode Wolf’s poetry. This being said, such ambiguous verse is also a joy for the reader or reviewer; there are as many interpretations as there are eyes to read. The poetry benefits from its bilingual presentation, with the German on the left and the English on the right as equal partners that reflect one another without simply replicating the other. This allows readers to appreciate the form and page-feel of both languages, even if they are not bilingual.

Something that struck me initially in Wolf’s German was the formatting: a reader of German would expect the nouns to be capitalised, but here they are not. This only adds to the possibilities of their ambiguity, as words which could be both nouns and adjectives, or nouns and verbs, are no longer distinct from each other; the line einen gehorsam verzeichnen could mean, as Nissan has translated it, “to register an obedience”, but equally could have been translated as “to register (somebody/something) obediently”. The German prose is made ever denser by this use of the language, as the nouns no longer jump out on the page. While reading the German poems, I realised with a start that this is what reading English may have felt like to my German-speaking students, learning to read a language in which the nouns blend in with everything else. READ MORE…