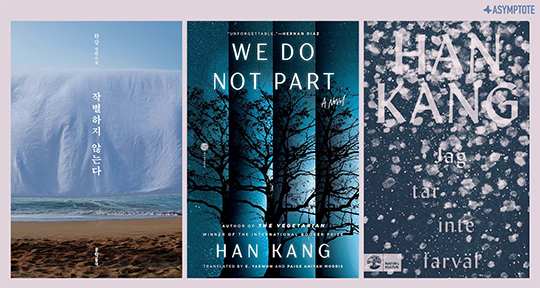

Behind the walls of the publishing industry, countless decisions are made to bring our favorite novels to our shelves. These decisions grow ever greater when it comes to translations, and particularly translations into languages other than English. In the following essay, Linnea Gradin explores the complex process of bringing Korean literature to Sweden, featuring commentary from Swedish translators and publishers in her analysis of monumental author Han Kang’s latest release in translation: 작별하지 않는다/Jag tar inte farväl/We Do Not Part. Discussing indirect translation, questions of form, and even the choices made in translating a single word, Gradin presents both the burdens and blessings of such a unique language pair.

Han Kang, one of South Korea’s biggest international authors, broke into the English-speaking literary fiction space with a bang in 2016 when she won the International Booker Prize for The Vegetarian (originally published in 2007), a darkly insightful look at Korean society told through the story of a woman who one day decides to stop eating meat in a quiet act of resistance that turns increasingly obsessive. That same year, Human Acts (originally published in 2014)—a novel that delves into painful parts of the country’s past—was also published in English, further cementing Kang as a leading voice of Korean literature worldwide.

Born in the city of Gwangju (where Human Acts is set), Kang is from a family of writers: her father is a teacher and award-winning novelist, and her two brothers are writers too. Kang herself has been widely praised and won many prestigious awards both domestically and internationally, and is known for her ‘poetic’ yet spare and quiet style among Korean readers. In her work, she often comes back to themes of remembrance and Korean history, approaching the subjects in a deeply empathetic though notably neutral way, never telling the readers what to feel or think. After winning the Booker Prize, her work—particularly the English translations of The Vegetarian and Human Acts by Deborah Smith—found itself at the center of discussions about the complexities of translation.

With her latest book, We Do Not Part, scheduled for English-language publication in January 2025 (almost a year after it was published in several European countries), I again find myself reflecting on translation and publication practices—and how different stories are mediated across different parts of the world.