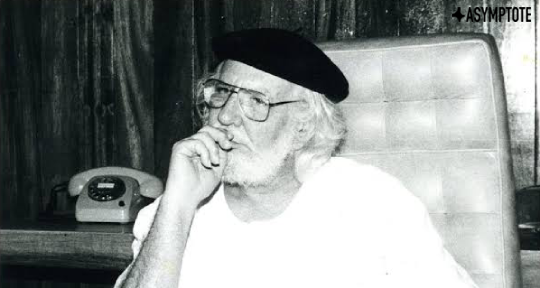

Maciej Hen is a well-known writer in Poland, awarded the Gombrowicz Literary Prize and shortlisted for the prestigious Angelus Central European Literature Award. Perhaps because the twentieth century was cruel to his Jewish family—himself being persecuted as a child in 1968 when the Polish government launched a campaign against the Jews—the writer writes primarily historical novels, describing the world at the precipice of immense change. In his debut work, According to Her, readers observe the birth of Christianity; in the following Solfatara, he describes ten days of revolution in mid-seventeenth-century Naples; in the third, a lonely, older hero from Warsaw goes on an unplanned journey amidst a change in regime, and discovers that his ancestor was at the head of a bloody people’s rebellion. Hen told me that in a new work—one which is not yet published—Doctor Faustus will be written as a woman. It seems to me that if the books of Maciej Hen were to be widely translated into other languages, he would become a contender for the Nobel Prize; his writing is visionary. With According to Her to be published soon in English translation by Holland House Books, readers in the Anglophone will now be introduced to this beautifully written book about the alternative life of Jesus Christ, told from the perspective of his old Jewish mother. I was moved and delighted by it; someone finally gave the voice to the Virgin Mary.

Wioletta Greg (WG): In According to Her, the story of a son is told by nearly a woman named Mariamne, who is almost a hundred years old, and uncannily resembles Mary of Galilea. A bold idea for an author who lives in a Catholic country.

Maciej Hen (MH): Not only do I live in a Catholic country, but worse still, I’m a Jew living in a Catholic country. And, to top it all, I’m a Jewish atheist. Actually, I grew up separated from the basics of Judaism, because my parents belonged to the first generation of Jews who felt that religion was not so important for their children.

WG: I’m curious why you published your book under the pen name Maciej Nawariak. Were you afraid of being attacked for re-describing the life of Jesus from a Jewish perspective?

MH: I took the pen name from pure vanity. My father is a writer who had earned himself a reputation long before I came up with my debut book, and I was so sure my publication would be a success, that, in order to fully enjoy it, I would have to disqualify in advance any suggestions people might put forward about my father’s name helping me enter the literary world.

WG: Your parents survived the Holocaust as refugees in Central Asia, and they met in Uzbekistan.

MH: Yes, they met in Samarkand in 1943. My mother was twenty-one at the time, and my father just under twenty. He was from Warsaw, and she was from a village outside Lwów. After the Nazis attacked the Soviet Union, they both evacuated eastwards and finally settled for a while in Samarkand, the former capital of Tamerlane. After the war, they returned to Warsaw. Out of their families—both once very large, as per custom—only five people survived, including themselves. My father changed his surname from Cukier to Hen, in time becoming a highly regarded writer in Poland, and my mother took care of the household, raising my sister and me—for a few years she was also a Russian language teacher. READ MORE…