For all its punishing workload, translation can be a thankless task, and translators are often the unsung heroes. This is especially true when it comes to breathing fresh air into a work of medieval literature wherein the translator perseveres with a bygone zeitgeist that challenges his artistic and literary prowess alike. To say that writing and translation are inextricably linked is to state the obvious. Sometimes, however, the translator needs to reexamine the history through the lens of literature and vice versa. The most ingenious translators aren’t the ones who faithfully rewrite the original work in the target language, but those who creatively reimagine it as well. In doing so, they might have to gingerly zigzag their way through a stilted language drenched in obsolete words that nevertheless communicate timeless ideas. In one such case, Mahmoud Rezvani, an Iranian scholar, teacher, and literary translator, has been able to do exactly that—bringing Sa’di’s Golestan, a work of classic Persian literature, to life in all its austere grandeur by preserving the rhyme in the poems and the musicality in the rhymed prose in ways never done before.

Abu-Muhammad Muslih al-Din bin Abdalah Shirazi, better known as Sa’di, was a thirteenth century Persian poet whose plangent poetry and compassion for humanity once received effusive encomium from the likes of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Even the oft-quoted opening lines of Whitman’s Leaves of Grass—I celebrate myself, and sing myself / And what I assume you shall assume / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you—have arguably been inspired by Sa’di’s timeless bani adam poem.

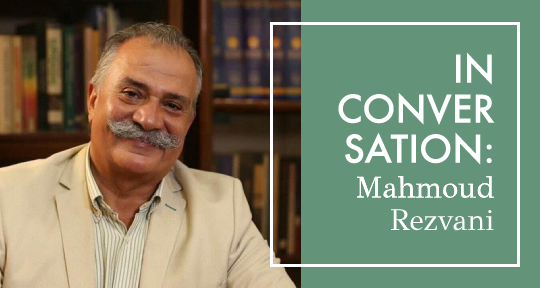

Rezvani is sixty-six now, with a salt-and-pepper handlebar mustache and a gregarious affect. He first began teaching in 1971 at the age of seventeen, and has since taught through such turbulent times as the Islamic Revolution, the Iran-Iraq war, and now the COVID-19 pandemic. “I still remember the very first air strike in Tehran during the war,” he says, “and I even remember what exactly I was teaching that day.” Still, Rezvani has never relinquished his sanguine attitude over the years. In the classroom, he is well known for his exuberance, oratorical bravura, and improvisational teaching style. Beyond that, his Renaissance-man bona fides—he has had serious grounding in math, Persian calligraphy, awaz (traditional Persian singing), literature, and martial arts—are also worth noting, most of which have served him well in his preparation for translating Sa’di.

Starting in 2008, the translation took Rezvani ten good years to finish. In March 2016, in an interview with Exchanges: Journal of Literary Translation, he cited “love” as the most important driving force behind his labor. That same month, he gave a first public reading of his translation at the University of California, Berkeley. Among the attendees were former US poet-laureate Robert Hass and his wife, poet Brenda Hillman, a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, both of whom applauded the decade-long effort. Since then, Rezvani’s translation has been endorsed by UNESCO and published—quite apropos to Sa’di’s hometown—by the University of Shiraz.

Our conversation took place on two separate occasions, and with diametrically opposite vibes. For the first part of the interview, I met Rezvani at his office after his last online class of the day which had ended around 10 pm. He was characteristically lively and rather voluble in his responses. For the second part, however, a somber mood was on full display during our discussion, following the death of Grand Maestro Mohammad-Reza Shajarian—Iran’s most internationally recognized awaz songster—who happened to be Rezvani’s longtime and beloved friend.

Siavash Saadlou (SS): How did the decision to translate Golestan come about? Why did you begin in 2008 and not sooner or later?

Mahmoud Rezvani (MR): I considered translating Golestan several times, but I was too afraid to give it a shot. Part of this had to do with my perfectionist nature, and part of it had to do with the enormity of the task. But an interesting incident gave me the belief that I could translate Golestan after all. About twenty years ago, Mohammad Hoghooghi, the late poet and literary critic, had a niece living in the United States who was getting married. He had written a letter in Persian for the wedding, and he needed someone to translate it into English, since his niece understood very little Persian. The letter was filled with purple prose, and Mr. Hoghooghi couldn’t find the right translator for the job. One day, he came to my language institute and asked if I could translate the letter. When I did translate the letter, it became somewhat of a sensation in small literary circles in the US at the time. Flash forward six months, Mr. Hoghooghi invited me to a get-together where many renowned Iranian translators were present. The moment I entered, he introduced me to everyone as “the one who translated the impossible,” and this served as a huge confidence-builder for me. That was the first time I seriously considered translating Golestan.

You asked me why I didn’t put off the translation until later, and I can only think of Sa’di’s own words from one of his poems, about how none of us can be sure if we would still be here in this world when the next spring comes around. That’s why I told myself, there’s no time like the present, and began to translate the book. When I first started working on Golestan, I never thought it would take me a decade to finish it. I still teach full-time, so I can’t solely focus on translation. When I was working on Golestan, I mostly translated on Thursday afternoons sitting in my office. Sometimes I used to translate as many as ten or twenty lines at a time, and other times I struggled with one particular page, even a single word, for days. READ MORE…