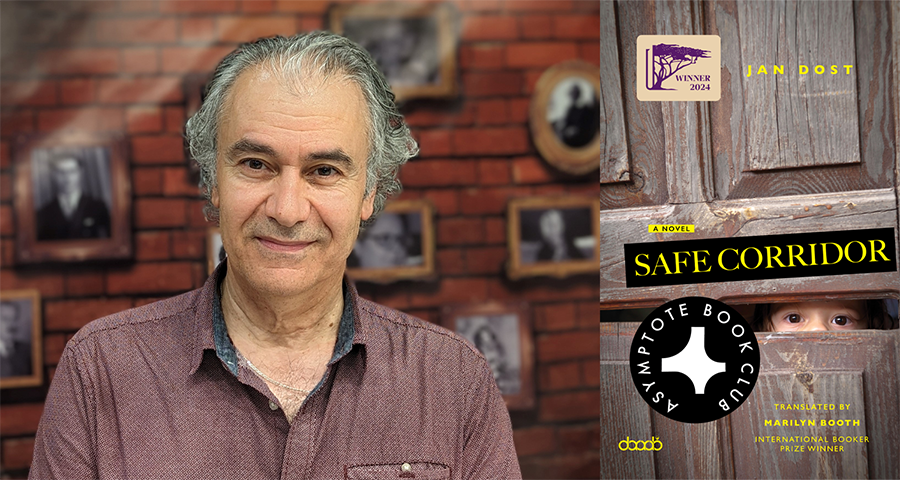

Syrian writer Jan Dost’s Safe Corridor is a searingly surreal portrait of the physical and psychic wounds that war inflicts on the most vulnerable among us. Narrated with lyrical intensity by thirteen-year-old Kamiran, the novel blends the brutal reality with Kafkaesque metaphor, depicting Syria’s painful conflict and the ways by which its abhorrent violence is processed and internalized. Furthering this work’s poignant impact is its lucid, flowing translation by renowned author and translator Marilyn Booth; in this interview, she speaks to us about remaining faithful to voice, handling stylistic variations, and her much-admired history with Arabic literature.

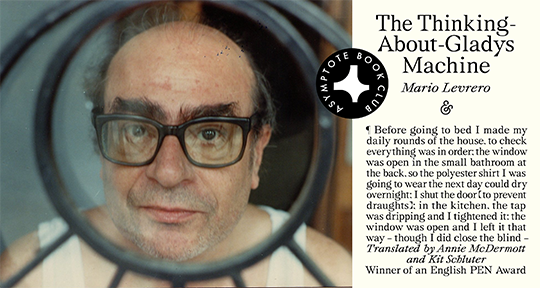

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Ibrahim Fawzy (IF): What first drew you to Safe Corridor and to Jan Dost’s work in particular?

Marilyn Booth (MB): I first met Jan at the Emirates LitFest in Dubai, just before the COVID pandemic. We had a wonderful conversation about literature and life, and I left with a couple of his books. When I read Safe Corridor (ممرّ آمن), I was absolutely blown away. Since then, I’ve read several more of his novels, though not all of them yet.

Jan is not only prolific but remarkably versatile—a poet, a novelist, a memoirist, and he also writes compelling historical fiction. Distinctive narrative voices are what most draw me, as both reader and translator, and that is precisely what I found in Jan’s work. He is a meticulous stylist, with hardly a wasted word. For a translator, that makes the work more demanding, but also deeply rewarding. READ MORE…