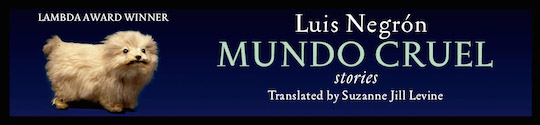

Luis Negrón’s short story collection Mundo Cruel, recently translated into English by Suzanne Jill Levine, has met the acclaim it well deserves. The first translated work to win a Lambda Literary Award for gay general fiction, Negrón’s debut book is an exceptional merging of absurdist humor (one story chronicles a man’s desperate attempts to have his dead dog stuffed), naturalism (the characters’ voices instantly take shape, come to life), and melodrama. In an interview with translator Suzanne Jill Levine, winner of PEN USA’s Translation Award, Levine discusses what drew her to Negrón’s work, and her career as a writer, translator, and educator.

Eva Richter: How did you first learn about Luis Negrón’s work, and how did you come to translate him?

Suzanne Jill Levine: Out of the blue I received an email from a young editor at Seven Stories Press, Gabriel Espinal, asking me to consider translating Mundo Cruel. The stories and the author, Luis—who is now a dear friend—were totally unknown. At first glance through the book, I was skeptical. Then Gabe invited me to visit him in NYC to talk about it. I was touched by his enthusiasm, the story of how he discovered Luis, and I felt admiration for the work of Seven Stories Press, and so I agreed to do a sample.

As I began translating, I found myself smiling and even laughing as I went along. A miracle: I had discovered a new writer who had a sly sense of humor, and who was dealing with such a destitute, sometimes sordid microcosm, which in his hands became a rich kasbah of living speech, ordinary yet extraordinary characters, depicted with pathos, wit and penetrating wisdom. I was sold.

ER: Mundo Cruel recently won the 26th Lambda Literary Award for gay fiction. Could you speak a little about contemporary LGBT literature in English translation?

SJL: I cannot comment authoritatively on this, though I presume that LBGT literature receives more recognition now than when I began translating in the 1970s. Translations in general have a double challenge in an English-speaking world—or should I say marketplace—where publishing literature even written originally in English is getting more and more difficult. I wasn’t aware, either, that Lambda had never in its history awarded a [fiction] translation, though I was struck by the fact that mine was the only translation considered this year. Maybe Lambda should add a category for works in translation? Anyway, in the context of Latin American literature, I was among the first to seek out and translate gay writers Severo Sarduy and Manuel Puig, subversively marginal among the Boom writers such as Garcia Marquez—and can only hope that this helped paved the way for others. Puig, from Argentina, was an important pioneer and spokesman for Latin America in this respect.

ER: What were some challenges you faced when translating Mundo Cruel? There are two short stories told by narrators speaking on the phone, using slang, colloquialisms, which I thought specifically must have been demanding.

SJL: The challenges are precisely what make translation worth doing, but yes, the language in these stories is often a very private language, spoken by a particular group in a particular barrio of San Juan. All the stories are “spoken” with the author as eavesdropper, but there is actually only one in which the narrator is speaking on the phone and it is hysterical because the reader hears only one side of the conversation, a device Manuel Puig used in Betrayed by Rita Hayworth. The main character, the speaker, is gossiping about “La Edwin,” for example: “The thing is that La Edwin fell for this little ‘Che Guevara’ and she’s got it bad… but when it comes to you-know-what the big machetero can’t even use his machete in the name of the Cuban Revolution… No, girl. That’s not the problem. It’s that the guy was and is straight.” Etc. The best way to explain to you is to show you, right? I also recommend that you read my book The Subversive Scribe: Translating Latin American Fiction, in which I recreate the process of translating slang, puns, and other “impossibles.” In a sense your question is like asking how a musician performs a piece of music; it’s a matter of ear.

ER: Did Luis Negrón engage in the translation process?

SJL: Luis, whose English is great, was a wonderful collaborator and the perfect source, of course, for any questions I had about gay slang, meaning, register, tone: we basically hunkered down for three days in a friend’s apartment in NYC and went through the manuscript. I also went over the text with another Puerto Rican writer and colleague in Santa Barbara, Leo Cabranes-Grant.

ER: A number of contributors to Asymptote blog have discussed Americans’ “lack of interest” [Nicolás Kanellos] in Spanish-language literature. Javier Molea, of McNally Jackson, said, “With few exceptions, there is no connection between the Spanish literary world and the English one. Any literary event in Spanish is allocated to the community events section of the newspaper, while a literary event in English is highlighted in the culture section.” As an acclaimed translator of Manuel Puig, Jose Donoso, and now Luis Negrón, what are your thoughts on this topic?

SJL: I think that what Javier is trying to say is that writers play a more important role in Spain and Latin American countries than they do in the United States (I hesitate to speak for Canada and the UK). A literary event in Bogotá will probably bring in a larger audience than in lower Manhattan. A greater problem is that there are fewer and fewer readers interested in serious or innovative literary works. Here and there a significant writer receives recognition, but more often, from what I’ve observed, there seem to be certain fashionable writers who come to represent their culture or nation in the global marketplace, mainly because of a generally superficial knowledge we have of literature as well as of other cultures and countries. Tim Parks has written on this topic, and I think he is completely accurate.

ER: Regarding the diminished appreciation of serious or innovative literature, why do you think that is? How has it affected your work?

SJL: In part I am speaking as an educator regarding this sense of a diminishing literary readership. My friends in publishing have plenty to say about this problem as well. In the past 30 odd years in academe I have watched the Humanities lose ground to the Social Sciences, but even more so, I have watched generations of students turn from the written word to the video/digital world: they are becoming increasingly illiterate, either uninterested or unable to read.

Obviously there are elite groups that continue to cultivate the study and appreciation of literature, and of course many will say that literature is evolving into other equally creative forms—and no doubt some of this is true.

How does the diminishing interest in literature affect me? There are fewer books I want to translate and fewer opportunities for publishers to translate the works of writers I like.

This being said, I am working more with poetry—and have discovered wonderful new poets from Mexico, Cuba, and Nicaragua—and also on my own creative non-fiction. After all, translation is a rite of passage, as someone once said. In 2012 I came out with my first poetry chapbook (Reckoning: Finishing Line Press), which brings together poems I’ve written with poems I have translated—and the translations seem almost more autobiographical than the originals…

ER: Do you have a translation philosophy that guides your work? How did it serve you (or not) in your translation of Mundo Cruel?

SJL: The Subversive Scribe speaks about translation as creation or “transcreation.” A writer, a translator succeeds in creating when s/he finds a voice: I would say that this happened in the translation of Mundo Cruel, but only you, the reader, can tell me if this is true.

***

Suzanne Jill Levine’s acclaimed translations, which include books by Guillermo Cabrera Infante (Three Trapped Tigers) and Manuel Puig (Betrayed by Rita Hayworth), have helped introduce the world to some of the icons of contemporary Latin American literature. She is also an editor of Penguin Classics’ essays and poetry of Jorge Luis Borges and the author of The Subversive Scribe: Translating Latin American Fiction. She is the winner of PEN USA’s Translation Award 2012 for her translation of Jose Donoso’s The Lizard’s Tale.