After our feature on studying language in South Asia on the eve of the seventieth anniversary of Indian Independence, we focus once again on the complex social and linguistic landscape of the subcontinent. Sneha Khaund reviews Man Booker Prize shortlisted author and Ordre des Arts et des Lettres awardee Initizar’s Hussain’s loving, nostalgic account of Delhi that has been recently translated by Ghazala Jamil and Faiz Ullah and published by Yoda Press. The Pakistani author (1923-2016) is widely recognized as a great Urdu writer and was a regular literary columnist for Pakistan’s leading English-language daily Dawn. He migrated to Pakistan in 1947 after it was created by partitioning colonial era India into the two nations of India and Pakistan. Hussain’s acclaimed novel Basti, published in 1979 and later translated into English, addressed the history of Pakistan and the subcontinent. As this review argues, the issues of secularism and language politics are as important in contemporary times as they were during the Partition.

As I reflect on the themes of the book I wish to dwell on in this review, my attention is interrupted by bits of information pouring in through news channels and the internet. A self-styled godman has been convicted of raping two of his former disciples. His followers are spread across Haryana and Punjab, neighbouring states of Delhi where I am writing from. The judgement has come fifteen years after the charges were made, during which period he has cultivated a flamboyant personal image, complete with movies and music videos. On Friday, the time leading up to the verdict was fraught with tension as the media speculated whether his followers would riot if he was convicted. The police had emergency preparations on stand-by, including three stadiums to hold people after arrests. Violence erupted after the verdict, as feared, and at last count, thirty people have died. Curfew has been imposed on parts of northern India and there has been an internet block-out in certain parts so that rumours don’t spread and incite fresh violence.

The deafening silence in the wake of violence in the modern state—whether it is Darjeeling, Kashmir, Punjab, or Haryana—is with what Intizar Hussain begins Once There Was a City Named Dilli. Hussain starts the first chapter by saying that he had arrived in Delhi “two and a half or three years after Partition” (3) and had headed to the Dargah of Hazrat Nizamuddin where he was taken aback by the silence that greeted him instead of the usual hustle and bustle. His surprise will be relatable to modern day readers familiar with the shrine of the Sufi saint in the heart of Delhi that draws throngs of devotees and tourists alike and is located close to one of the busiest railway stations in India. We wonder if a hush has fallen over the city in the aftermath of the violence of Partition, but Hussain draws a larger arc of history.

As he searches in vain for the nineteenth century Urdu poet Ghalib’s grave while the melancholy scream of a lonely peacock tears through the “dusk of that sad evening” (6), he is struck with amazement at how many times the city has been plundered and resettled. Thus begins Hussain’s quest to write the history of Delhi as a series of plunders, conquests, settlements. “Who were the settlers, who were settled?”, he writes. As scholars such as Romila Thapar have shown, these are complex questions because they carry within them the issue of who is the legitimate citizen of India. Both colonialist and nationalist historiography have been guilty of perpetuating the perception that Islam came to India by way of the sword, through figures such as Nadir Shah and Timur. Hussain then proceeds to draw up a historical narrative of the city from the time of the mythical Pandavas of Mahabharat, the period of Islamic dynasties, the colonial era where India’s capital was shifted to Delhi from Calcutta in 1911, ending finally with the nationalist movement in the early twentieth century that eventually led to the creation of two nation states—India and Pakistan.

READ MORE…

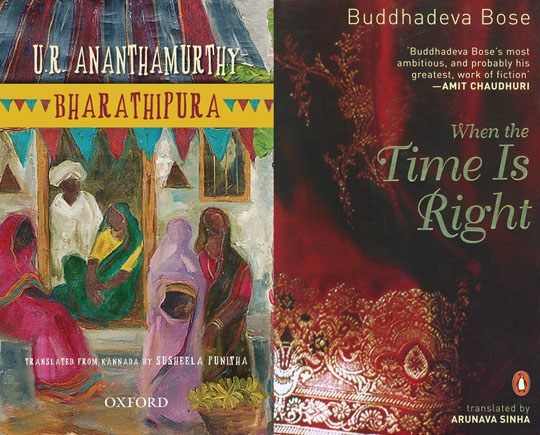

It’s Time to Talk: On Translations from South Asian Languages

Mahmud Rahman concludes his insightful series by addressing your questions and responding to the discussion he sparked.

Read all posts in Mahmud Rahman’s investigation here.

In this final post, I want to respond to some issues that have come up among readers. Besides a few comments on the blog posts, this series also generated conversations that came to me via personal emails or messages on Sasialit, a mailing list about South Asian literature.

Huizhong Wu, a literature student at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote me:

READ MORE…

Contributor:- Mahmud Rahman

; Tags: - comments

, - discussion

, - South Asian languages

, - South Asian literature