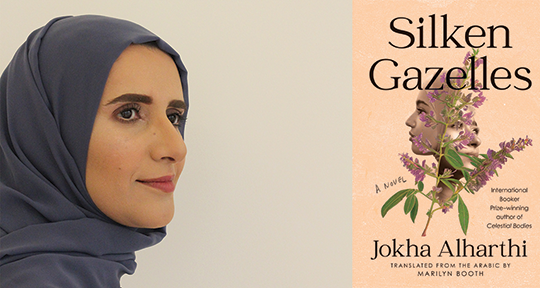

Silken Gazelles by Jokha Alharthi, translated from the Arabic by Marilyn Booth, Catapult, 2024

The acclaimed Omani writer and academic Jokha Alharthi has emerged as an increasingly significant voice on the international literary landscape since her novel, Celestial Bodies (translated by Marilyn Booth), was awarded the International Booker Prize in 2019. Now, once again, Catapult Press has opened the floodgates to another tentacle of the Omani society in the form of Alharthi’s fragmented worlds. In her latest novel Silken Gazelles, also gracefully translated by Booth, a wide net reins in the past to the present, the village to the city, sisterhood to motherhood, and love to loss. The dreamy and nonlinear narrative moves forward and backward in time, treating generations as flexible containers and relying on polyphony to create a poetic geometry of voices.

Tellingly, the intertwined threads of the narrative are captivating from the very beginning; extremely concise hints are made in the early chapters towards the throughline, but the hints are almost complete in themselves. At the end of the first chapter, for instance, Ghazaala’s life is wrapped up in a few sentences. “Within five years [she] had given birth to twins,” writes Alharthi, “finished her secondary education, and entered the university. In her final year of study in the College of Economics, the Violin Player ran away from the house of marriage.” In a similar vein, in the second chapter, when talking about Ghazaala’s foster mother, Saada, Alharthi writes:

It would have seemed so ordinary, so natural, for Saada to live to be a hundred years old. For Saada to always be there, preparing maghbara for the cow and coconut sweets for the children, drawing milk and cream, feeding Ghazaala and Asiya and Mahbuba and the goats, undoing her hair and baking as she sang, exuding a fragrance of incense and fresh dough, laughing her ringing laugh, and forever gathering the plants that could treat poisons and fevers from the high slopes surrounding Sharaat Bat. . . But Saada never made it, not even to thirty.