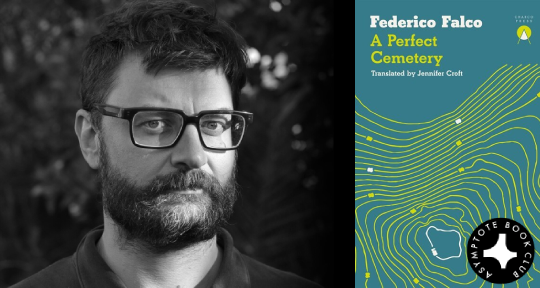

In our Book Club selection for the month of April, A Perfect Cemetery, Federico Falco’s writings do not tell so much as unfold, gently and masterfully, to elucidate the relationships between the human, the non-human, and the spaces in which such meetings take place. In precise and rich evocations, Falco plumbs the rich vocabularies and intrigues of landscape to lend delicacy, sensuality, and vividity to his prose, bringing his protagonists to life with a knowing rootedness. In the following interview, transcribed from a live Q&A hosted by Assistant Editor Shawn Hoo, Falco and translator Jennifer Croft share their thoughts on the cinematic aspects of A Perfect Cemetery, the relationships between the body and the land, and the pervading theme of isolation.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive Book Club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom Q&As with the author and/or the translator of each title!

Shawn Hoo (SH): I thought we could begin with the question of place. I read this book in Singapore, a dense city, and noted how A Perfect Cemetery has a distinct sense of place; Federico, you conjure a landscape of sierras, rivers, and forests across disparate short stories that belong to this very single novelistic world. In an interview with The Paris Review, Jennifer, you emphasize the importance of translators visiting the country they are translating from. How does your sense of place affect your approach to these stories?

Federico Falco (FF): Landscape transforms us and makes us different people; the people who live in big cities have one kind of experience of life and the people who live in different landscapes have another. There is an Argentinian writer, Juan José Saer—one of my favorites—who says that the poor who live in cities near the ocean, they have a heaviness; they become used to strange, different people arriving and leaving all the time. And the people who live in the mountains always think that there’s another place beyond the mountains. They can change their point of view because they can see things from a different point of view. The people who live in the plains here in Argentina, the Pampas, they see the same landscape all the time. They can walk ten kilometers, and the whole scene shifts ten kilometers.

So when I write, I try to think about where the character lives, where they grew up, what they need, where they differ, what was new for them—if they grew up in the plains and now live in the mountains. I used to live in the city, now I’m living in the mountains, and there are some things that you can feel in the body. Your body starts to change. The air is different. The muscles change because you’re climbing all the time. The way you relate to people in the city is really different from the way you relate to people here in the mountains. If I meet a stranger here in the street, I say hello, which I never do in the city.

Jennifer Croft (JC): I really loved listening to Fede talk about place. Obviously, translating these stories influenced me as well, and I have been thinking a lot about place in fiction. Right now, I’m working on a book of creative nonfiction called Notes on Postcards, and part of the question of this text is: why does it matter where we are when we’re communicating with someone? Or why does it matter where we are in general? I started thinking about this question in 2020, when all of my travel plans were cancelled. I felt really cut off from all of the places that I care about—first and foremost among those is Buenos Aires. I feel very panicked that I’m not allowed to enter Argentina right now because of my US passport. I’m currently in upstate New York at a writing residency called Yaddo, and I’ve had a hard time working on my project, but thanks to these conversations with Fede over the last week or so, I’ve been relaxing into it.

I like comparing my obsession with places to Fede’s, because mine is less about landscape and more about cities and cultures. Even though culture is such an extremely fluid thing, it is much more about how one feels in the context of other human beings. I’m more of a flaneur kind of writer, and it’s great for me to be able to incorporate these landscapes into my thinking too. READ MORE…