This month in newly released translations, we’re featuring two authors of inimitable voice and style. From the Catalan, a surrealist masterpiece by Ventura Ametller sharply blends history with mysticism in an epic retelling of the Spanish Civil War; and from the French, the latest text by Annie Ernaux returns to some of the author’s most central themes—sex and memory—in a poignant examination of corporeal and psychological navigations.

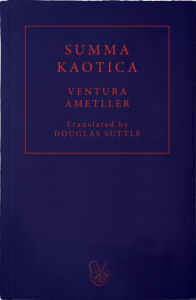

Summa Kaotica by Ventura Ametller (Bonaventura Clavaguera), translated from the Catalan by Douglas Suttle, Fum d’Estampa, 2023

Review by Samantha Siefert, Marketing Manager

A monstrosity of a fish gnashes at a tiger, the tiger leaps towards a gun, the gun is aimed perilously at the prone body of a nude woman. . . It’s all so unexpected and moving, but what do these objects have to do with one another—or with anything at all?

Such is surrealism: the challenge of reconciling the disparity of absurdity. “Everything leads us to believe that there exists a spot in the mind from which life and death, the real and the imaginary, the past and the future, the high and the low, the communicable and the incommunicable will cease to appear contradictory,” declared André Breton in his manifesto. Riding on the coattails of Dadaism, surrealism emerged as an impulsive reaction to the tragedy of the First World War: If reason had resulted in such great suffering, then what good was a movement rooted in realism?

The antithesis of reason, then, was the way forward, and the efforts of the avant-garde were so resonant that they continue to exist today as comfortable figures of popular culture, where the discordance of fish, tiger, and gun feel almost familiar in Salvador Dalí’s famous painting, “The Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening.” The surrealist world of letters, however, leave room for discovery.

In Catalonia with Dalí at the beginning of the twentieth century, the writer Ventura Ametller—the pen name of Bonaventura Clavaguera—was hard at work, producing a prolific collection of poetry, essays, and novels that turn the world upside down in raucous prose, described by essayist Lluís Racionero as “Dalí in words.” His work has remained only quietly appreciated, but perhaps the time has come for that to change with the new publication of Ametller’s groundbreaking magnum opus, Summa Kaotica, in a masterful translation from the Catalan by Douglas Suttle. READ MORE…

Radical Reading: Sara Salem Interviewed by MK Harb

I’ve increasingly thought more about what generous, kind, and vulnerable reading might look like instead.

At the height of the pandemic, I—like so many of us—looked for new sources of intrigue and intellectual pleasure. This manifested in finding Sara Salem’s research and reading practice, Radical Reading, which was a discovery of sheer joy; Salem views books and authors as companions, each with their own offerings of certain wisdom or radical thought. When she shares these authors, she carries a genuine enthusiasm that they might come with some revelation.

I interviewed Salem as she sat in her cozy apartment in London wrapping up a semester of teaching at the London School of Economics. We discussed our lockdown anxieties and our experiences with gloomy weather until we arrived at the perennial topic: the art of reading. The interview continued through a series of emails and transformed into a beautiful constellation of authors, novelists, and activists. In what follows, Salem walks us through the many acts of reading—from discussing Angela Davis in Egypt to radicalizing publications in her own work, in addition to recommending her own selections of radical literature from the Arab world.

MK Harb (MKH): Reading is political, pleasurable, and daring. Inevitably, reading is engaged in meaning-making. How did you arrive at Radical Reading as a practice?

Sara Salem (SS): Some of my most vivid childhood memories are of spending long afternoons at home reading novels, and when I think back to those novels, I find it striking that so many of them were English literature classics. I especially remember spending so much time reading about the English countryside—to the extent that today, when I am there, or passing it on a train, I get the uncanny feeling that it’s a place I know intimately. Later, when I read Edward Said’s writing on Jane Austen and English literature more broadly—its elision, erasure, and at times open support of empire—it struck me that we can often read in ways that are completely disconnected from the lives we live. This tension was what first opened up entire new areas of reading that completely changed my life, among which was the history of empire across Africa; at the time I was living in Zambia, where I grew up, and often visited Egypt. Critical history books were probably my first introduction to what you call the practice of radical reading, of unsettling everything you know and have been taught in ways that begin to build an entirely different world.

I like that you say reading is engaged in meaning-making, because it has always been the primary way in which I try to make sense of something. Even more recently, as I’ve struggled with anxiety, reading above all became my way of grappling with what I was experiencing: what was the history of anxiety, how have different people understood it, and how have people lived with it? I realise, of course, that not everything can be learned from a book, but so far, I’ve found that what reading does provide is a window into the lives of people who might be experiencing something you are, making you feel less alone.

MKH: How do you reconcile reading for pleasure versus reading for academic and political insights? Do they intersect? Being idle has its own spatial practice of radicality at times, and I’m curious on how you navigate those constellations.

SS: This question really made me think! In my own life, I have always made the distinction of fiction as pleasure and non-fiction as academic/work-related. So, if I need to relax, or want to take some time off, I will instinctively reach for fiction, and if I want to start a new project, I think of which academic texts would be helpful. However, this began to change about five or six years ago, when I began to think more carefully about how fiction speaks to academic writing and research, as well as how non-fiction—unrelated to my own work—can be a great source of pleasure and relaxation. This has meant that they have begun to intersect much more, and it has enriched both my academic work and my leisure time. READ MORE…

Contributor:- MK Harb

; Language: - Arabic

; Places: - Egypt

, - Zambia

; Writers: - Ahdaf Soueif

, - Arwa Salih

, - Huda Tayob

, - Mahmoud Darwish

, - Sonallah Ibrahim

, - Thandi Loewenson

, - Waguih Ghali

; Tags: - intersectional feminism

, - migration

, - Race

, - radicalism

, - Reading

, - sexuality

, - social commentary