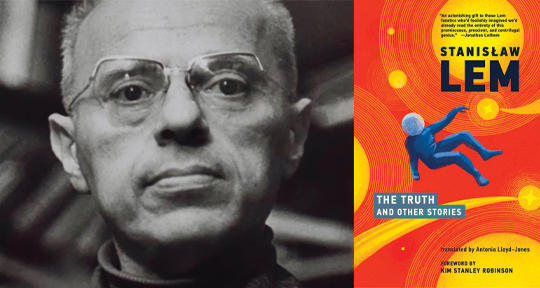

The Truth and Other Stories by Stanisław Lem, translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, MIT Press, 2021

One cannot overstate how profoundly our relationship with computers has changed since the mid-twentieth century. Once upon a time, the notion of a mechanical brain was as alien as the notion of, well, an alien. Similar to research of extraterrestrial life, there were then a few elite scientists, sequestered in institutions, who were better informed to predict what an encounter with a mechanical brain might entail than the general population, for whom such a concept was nothing more than fantasy.

Stanisław Lem was of that class. Son of a doctor, he studied medicine until his transition to literature. As a newcomer to Lem’s copious body of work, what surprised me most about this collection of previously untranslated stories was how, with very little attention to character development, he manages to render this scientific class with as much fidelity as their fields of inquiry. I expected their curiosity and ambition, even obsession, but not their yearning, inquietude, or melancholy. How disappointing that, when confronted with the other, we might not be able to communicate. But how utterly devastating that, when confronted with one of our own, we never are able to truly communicate. In The Truth and Other Stories, it is often this precise pathos that catalyzes action.

There’s inherent value in the defamiliarization of technology that comes from reading literature—especially speculative fiction—from a previous era. Lem luxuriates in the weight and texture of his machines. His favorites occupy rooms and require trips to many types of stores to build. Gels, wires, soldering . . . they are so tactile, until the moment—signaling the beginning of the end—they become more than the sum of their parts. In “The Friend,” a young member of a Short-Wave Radio Club gets caught up in the mysterious mission of a rather haunted man, Harden, who is driven to complete it for a highly secretive friend. While building the electrical structure called “the conjugator,” the boy’s affection for Harden grows as he tries to solve the mystery of the project, yet simultaneously begins to doubt the terms of Harden’s relationship with the absent friend. “The word ‘conjugator’ had come back to mind, which was what Harden had called the apparatus. Coniugo, coniugare—to join, to connect—but what did it mean? What did he want to join, and to what?” he wonders. The real possibility of friendship with Harden is constantly frustrated, ironically, by the bizarre circumstances of this connecting machine. What the technology promises of connection gets in the way of intimacy’s reality.

Harden pressed my hand to his chest with his eyes closed. In any other person it would have looked theatrical, but he really was like that. The more I cared about him—as I was fully aware by now—the more he exasperated me, most of all because of his lethargy and the cult of the ‘friend’ he nurtured. READ MORE…