This Translation Tuesday, we are pleased to present new short fiction from the Montenegrin author Tijana Rakočević. A surprise awaits—for this story takes place not in contemporary Montenegro, as one might expect from the author’s identity, but in Tanzania’s colonial past, during the Kashasha laughter epidemic of 1962. This hypnotic tale describes the outbreak of the epidemic in remote Tanzania following the arrival of a British agent. As the narrator returns continually to the central image of a vitiligo-mottled fawn, whose coloration is mirrored by that of the disabled protagonist, Andwele, a haunting parable of illness, dehumanization, and assimilation emerges, rendered here in elliptical but powerful English by Will Firth.

Wache waseme nimpendae simwachi.[1]

If you never leave the house, no tragedy can befall you.

The edges of Tulinagwe’s purple khanga danced in the air as she kneaded a ball of risen dough. Whenever eight-year-old Andwele, as piebald as a scrofulous calf, stuck his finger into his mouth so far that he could touch the back of his throat, she would snarl, You sure know how to get on one’s nerves, boy, but this time she held her tongue. He tested her patience by rocking on a loose wooden board on the ground that moved to the rhythm of his round heels, and he only stopped when his mother glanced at him; in those moments, he felt I’m the center of the world, but she—if she had the strength to speak—would have called it asking for a hiding. It was a holiday in all Kashasha: the white man, Sir Jonathan, had returned—a dissolute English bon vivant, who their Baba wa Taifa, their savior Mwalimu, Julius Kambarage Nyrere, had befriended in Edinburgh during his studies. Tulinagwe saw him out of the corner of her eye as he ambled along the main road escorted by a gaggle of black girls, and, if she had not been busy rolling the dough for the family, which was so thin that it kept breaking in the middle, she would have said, not particularly handsome, not particularly tall; instead, she decided, I’ll save salt; if they still like it, they can ask for more.

Andwele slipped and fell. It was a tragedy.

He remembered that Mwanawa had given him five shillings and he limped off through the yard. The women wanted him to leave the village, which he sensed in the way they prepared him for the trip and because they had whispered ever since Kyalamboka lived in Sir Jonathan’s house. The man’s collection of romantic safari oddments in his private residence—photographs with animals, human animals, and human humans—seemed a grotesque combination to him, who imagined Muleba district as a mind-bogglingly vast Tanzanian shilling: go banana picking, they would have advised him if he were older, I’ll go cotton picking like Ipyana, my dad, he thought, but he lacked the courage. After that unusual visit, he believed Muleba was a heart broken. Hidden in the bushes near the house, he tried to get a glimpse of the vitiligo fawn that bwana had brought as a trophy from Europe, a fawn they called Sekelaga, Joy, but it was not there; he just heard the titillated giggles of his elder sister that vanished in the warm breeze. What did he promise her, he wondered, and will he take her with him? He would notice a villager and hire them to scrub the floors, and he would look on that troglodyte as human—that was the fortunate circumstance that made them dignified in their own eyes. The foreigner, always well-meaning and amicable, as if his earthly life depended on that handful of semi-savages, offered him Abba-Zaba chocolates so he would keep the secret; Andwele first spoke hapana, hapana, later nasikitika, but he was captivated by the sweet pain in his throat: asante sana, he repeated more and more often, thank you very much. He went away calm and beaming, his face radiant like a young idiot, dragging along his leg that they broke four more times after the accident, only to conclude it was better to leave it. Kyalamboka watched her disfigured brother and snorted spitefully in her rich lover’s ear, that little freak—sometimes I’d like to trip him up.

Radical Reading: Sara Salem Interviewed by MK Harb

I’ve increasingly thought more about what generous, kind, and vulnerable reading might look like instead.

At the height of the pandemic, I—like so many of us—looked for new sources of intrigue and intellectual pleasure. This manifested in finding Sara Salem’s research and reading practice, Radical Reading, which was a discovery of sheer joy; Salem views books and authors as companions, each with their own offerings of certain wisdom or radical thought. When she shares these authors, she carries a genuine enthusiasm that they might come with some revelation.

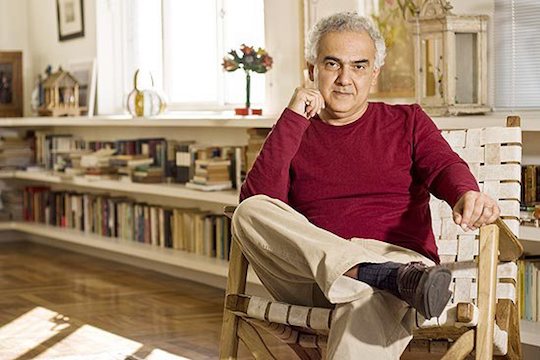

I interviewed Salem as she sat in her cozy apartment in London wrapping up a semester of teaching at the London School of Economics. We discussed our lockdown anxieties and our experiences with gloomy weather until we arrived at the perennial topic: the art of reading. The interview continued through a series of emails and transformed into a beautiful constellation of authors, novelists, and activists. In what follows, Salem walks us through the many acts of reading—from discussing Angela Davis in Egypt to radicalizing publications in her own work, in addition to recommending her own selections of radical literature from the Arab world.

MK Harb (MKH): Reading is political, pleasurable, and daring. Inevitably, reading is engaged in meaning-making. How did you arrive at Radical Reading as a practice?

Sara Salem (SS): Some of my most vivid childhood memories are of spending long afternoons at home reading novels, and when I think back to those novels, I find it striking that so many of them were English literature classics. I especially remember spending so much time reading about the English countryside—to the extent that today, when I am there, or passing it on a train, I get the uncanny feeling that it’s a place I know intimately. Later, when I read Edward Said’s writing on Jane Austen and English literature more broadly—its elision, erasure, and at times open support of empire—it struck me that we can often read in ways that are completely disconnected from the lives we live. This tension was what first opened up entire new areas of reading that completely changed my life, among which was the history of empire across Africa; at the time I was living in Zambia, where I grew up, and often visited Egypt. Critical history books were probably my first introduction to what you call the practice of radical reading, of unsettling everything you know and have been taught in ways that begin to build an entirely different world.

I like that you say reading is engaged in meaning-making, because it has always been the primary way in which I try to make sense of something. Even more recently, as I’ve struggled with anxiety, reading above all became my way of grappling with what I was experiencing: what was the history of anxiety, how have different people understood it, and how have people lived with it? I realise, of course, that not everything can be learned from a book, but so far, I’ve found that what reading does provide is a window into the lives of people who might be experiencing something you are, making you feel less alone.

MKH: How do you reconcile reading for pleasure versus reading for academic and political insights? Do they intersect? Being idle has its own spatial practice of radicality at times, and I’m curious on how you navigate those constellations.

SS: This question really made me think! In my own life, I have always made the distinction of fiction as pleasure and non-fiction as academic/work-related. So, if I need to relax, or want to take some time off, I will instinctively reach for fiction, and if I want to start a new project, I think of which academic texts would be helpful. However, this began to change about five or six years ago, when I began to think more carefully about how fiction speaks to academic writing and research, as well as how non-fiction—unrelated to my own work—can be a great source of pleasure and relaxation. This has meant that they have begun to intersect much more, and it has enriched both my academic work and my leisure time. READ MORE…

Contributor:- MK Harb

; Language: - Arabic

; Places: - Egypt

, - Zambia

; Writers: - Ahdaf Soueif

, - Arwa Salih

, - Huda Tayob

, - Mahmoud Darwish

, - Sonallah Ibrahim

, - Thandi Loewenson

, - Waguih Ghali

; Tags: - intersectional feminism

, - migration

, - Race

, - radicalism

, - Reading

, - sexuality

, - social commentary