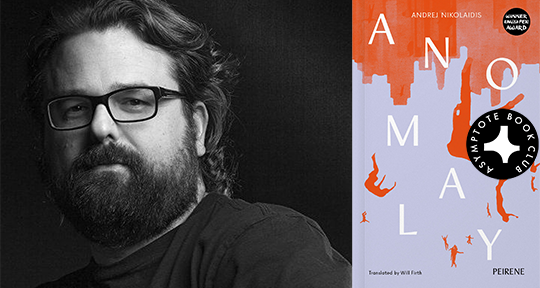

In Andrej Nikolaidis’ Anomaly, no one is safe. Not only is the world ending, but everything is being unearthed up along with it—every confidence, every disgrace, every deception. With his signature blend of rapturous imagery and indomitable intellect, Nikolaidis forces humanity to face its horrors while still allowing us some potential for redemption, a characteristically penetrating move for an author who is also an outspoken activist against war and corruption. Just last month, Nikolaidis faced intimidation and public harassment for his bold political work in Montenegro, underlining the necessity and urgency of his dissent. We are proud to announce this exemplary title as our Book Club title for the month. It’s a hell of a ride, literally.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Anomaly by Andrej Nikolaidis, translated from the Montenegrin by Will Firth, Peirene Press, 2024

I am an Apocalyptist. I believe that Good will win out in the end, and when it does, the world as we know it will be abolished—it will no longer exist. So, once that world is gone, Good will prevail. If the concept of the Apocalypse isn’t the ultimate irony, I don’t know what is.

—Andrej Nikolaidis

Andrej Nikolaidis’ Anomaly, published in Will Firth’s translation, begins with a verdict: “The human race owes its history, as well as its future, to the fact that we’ve always been able to turn our backsides to the graves of those we maltreated, and then seek absolution.” Though this has been the case for millennia, the novel insists that human censorship will not be able to preserve its euphemized retellings for much longer. After a freak incident involving “a machine that would give each of us . . . all of the possible scenarios and outcomes of our lives”, past and present begin to merge: a mammoth falls and crushes a man brooding on a quay in Chile; a cruise ship collides with three women contemplating shop windows on Ferhadija Street; a man haunted by an incestuous affair is killed by a cannonball fired in 1805 by Napoleon’s fleet, while praying in the Kotor Cathedral. The truth of never-ending human cruelty—“one drop” of which is “enough to destroy the world”—finally refuses the revisionism afforded to us by the present, and becomes unignorable by physically unfolding everywhere, all at once. Nikolaidis’ very literal rendition of the Book of Revelation is unflinching, darkly humorous, and relentless in its pursuit of the uncomfortable details we tend to suppress.

In 1992, Nikolaidis and his parents fled to Montenegro from his native Sarajevo to escape the mounting ethnic strife that would soon erupt into the Bosnian War; the author, then, is no stranger to the tumultuous experiences at the core of Anomaly. Decidedly anti-war and anti-nationalist, Nikolaidis is also fearless in voicing his views. When his 2006 novel, Sin, was awarded the 2011 European Union Prize of Literature, the announcement detailed how his public defense of “victims of police torture. . . resulted in his receiving many threats, including a death threat during a live radio appearance”. His insistence on “freedom of speech [as] the basis of freedom” is obvious in his literary and journalistic work—and the way he implements this freedom is equally noteworthy. READ MORE…