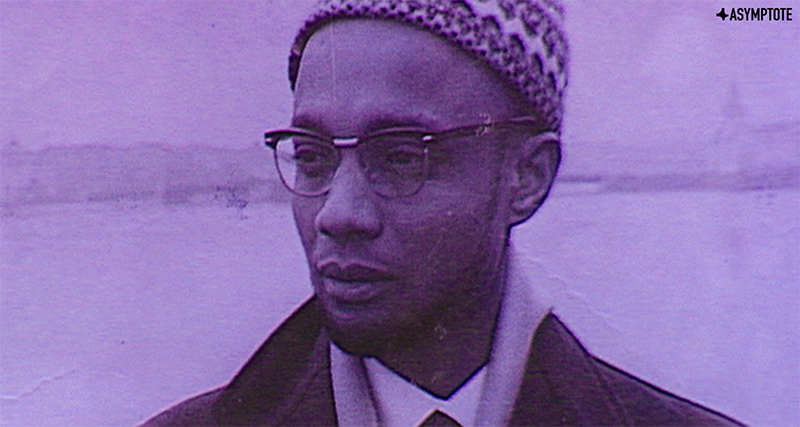

Poet, revolutionary, scientist, politician: Amílcar Cabral took many roles throughout his extraordinary life, including leading the nationalist movements of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. Admired for his staunch ideals and his uncompromising vision of pan-Africanism, many of his ideas continue to be found in anti-oppression rhetorics and movements all over the world. In this essay, Bethlehem Attfield takes a look at his legacy—one that has spread far beyond the African continent—fifty years after his nation’s independence.

This year, Cape Verde is celebrating a special milestone: the fiftieth anniversary of the nation’s independence. Yet, the celebrations actually began the year before, in honour of what would have been the hundredth birthday of the country’s founding hero, Amílcar Cabral (1924–73). Cabral was a political leader who founded the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), and led an armed struggle to free both nations from Portuguese colonial rule. While he is best remembered as a prominent anticolonial figure across Africa, Cabral also left a powerful legacy through his writing, poetry, and cultural ideas, many of which are collected in the volume Resistance and Decolonization, translated by Dan Wood.

Particularly intriguing are his theories concerning culture; he regarded the promotion of national spirit among the rural peasantry, whose lives remained unaffected by imperialism, as vital to national liberation. However, in terms of language use, he differed from most anticolonial leaders who condemn the destructive impact of colonial language on the cultural fabric and psyche of the colonised people. Instead, Cabral argued that the colonial suppression of cultural life in Africa was ineffective, writing:

Except for cases of genocide or the violent reduction of native populations to cultural and social insignificance, the epoch of colonization was not sufficient, at least in Africa, to bring about any significant destruction or degradation of the essential elements of the culture and traditions of the colonized peoples.