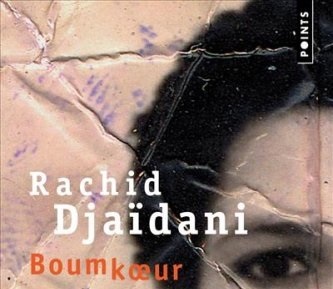

For this week’s Translation Tuesday, we bring you an extraordinary new work of microfiction by the Guianese poet Mireille Jean-Gilles. Stranded in the central yard of a nameless school, Jean-Gilles’ narrator is confounded by the ugliness and hostility of the buildings’ facades. They assume that the institution they face must be a factory or a prison, so at odds are they with the purpose of a school, and the emotional lives of young people. Yet even as the school is an institute of dehumanization, it still carries prefigurative possibilities: “I sensed that each class must have been an oasis of happiness, full of colors, full of children’s drawings, of colors, from dreamy blue to impulsive purple, a thousand childish colors.” The narrator’s voice spills over with questions in the face of this contradiction, phrases and clauses accumulating one after the other, piled paratactically like the “wildly green leaves” of the mango tree in the schoolyard. They are adrift in this strange place, yet ultimately their dislocation is a source of peace, as they resign themself to the paradox of beauty emerging in a hostile world: “everything was one and its opposite at the same time . . . so I searched no more, just let myself be carried away by the swell of waves.” Read on!

It wasn’t a factory, or a prison, although you might have thought so, it was immense, full of cells, full of rooms, in fact, finally, it seemed to me that it was only a mundane school, it wasn’t the end of a shift, it was only the end of classes, classes for shrill little children or mocking older ones. The prison, sorry, the school, had in its center a navel, an immense navel that must undoubtedly have been what’s called a schoolyard, the schoolyard was finally mute since within ten minutes the entire school had emptied, the signal had been finally given to clear out, it was five o’clock.