“Pulling narratives together is an act of blind construction, an exploration of the valid. Constructions suggest artificiality. And it is true, in legal prose terms, that poems, as constructions, are artificial and therefore unreliable. But poets should not be afraid of construction: construction is the poem’s natural way of witnessing.”

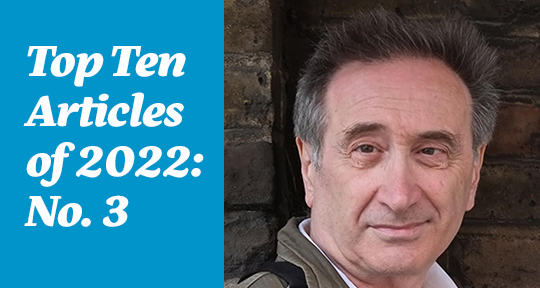

Acclaimed poet and translator from the Hungarian Georges Szirtes comes in at Number 3 in our countdown of the most-read articles of the year, via his interview in the Winter 2022 issue. Renowned for both his poetry as well as for his translations, Szirtes writes prolifically and without pretense in print and on social media. As a translator, Szirtes is perhaps best known for his work on Hungarian phenom László Krasznahorkai (his translation of Satantango won the Best Translated Book Award in 2013; while you’re here, why not also read our interview with László Krasznahorkai?).

In her brilliant interview, our very own Rose Bialer reveals Szirtes to be a poet grappling with and exploring constraints—of memory, borders, mortality. Szirtes offers intimate insights on the lasting impact of his experience of migration in childhood and the memories—“small fragments of coloured glass that may—with a lot of luck—add up to a stained glass window of sorts”—that he has pieced together from the family photographs that he carried on the journey from Hungary to England. These memories drove Szirtes to reclaim the Hungarian language twenty-eight years after it “went to sleep.” Visualizations of what might have been permeate Szirtes’ poetry; taken as a whole, his collections reconstruct the story of his life, with glimpses of reality that appear as if frozen in film.

For example, of his latest work Waking in the Yellow Room, Szirtes says:

These are exercises of the imagination based on my experience of him [my father] and on my own sense of what Jewishness entailed for him then and what it entails for me now . . . The yellow room is the house of the soon-to-be dead. I see him as the child squatting in the corner.

In this experiment, Szirtes rewrites the constraints of memory, suggesting a new reality in which his father didn’t eschew Judaism for Atheism in the traumatic aftermath of the Holocaust. In addition, “there are increasing reminders of mortality as one grows older; in my case the death of friends, the pandemic, my own state of health . . . my mother’s early death . . . I have been sure from the start that the apprehension of mortality is what drives the whole artistic project.”

This is not the first time Szirtes has been featured in Asymptote, his poem The Swan’s Reflection: two sides of a postcard headlined our English Poetry Feature as far back as in our Fall 2011 issue, alongside Lydia Davis’s very first translations from the Dutch, new translations of Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz, and a survey of Croatian novelists by Dubravka Ugrešić. Find contributing editor Sim Yee Chiang’s behind-the-scenes look at this issue from our #30issues#30days showcase. If you’re inspired to submit your own work after dipping into our twelve-year-old archive, check out our submission guidelines here and send in your best work today!

CLICK HERE FOR OUR THIRD MOST-READ ARTICLE OF 2022

*****

Discover more on the Asymptote blog:

- Our Top Ten Articles of 2022, as Chosen by You: #4 Envy by Elfriede Jelinek

- Our Top Ten Articles of 2022, as Chosen by You: #5 The Hundred-Faced Actor by Edogawa Ranpo

- Our Top Ten Articles of 2022, As Chosen by You: #6 An interview with Maureen Freely

We Stand With Ukraine: “The Ghost of Kyiv” by B. R. Dionysius

Through his phone’s / cracked canopy he plays you a black streak / over Kyiv

In this week’s edition of literary works written in support and solidarity with the citizens of Ukraine, we are proud to present a poem by B. R. Dionysius. “The Ghost of Kyiv” movingly comments on the distancing voyeurism of watching tragedy unfold from afar, and of wide-ranging human affairs condensed into byte-sized consumption. As we continue to navigate the ever-shifting boundaries between the virtual and the real, Dionysius’ poem works between man and machine, its precise lines edging out the bodies caught within them.

The Ghost of Kyiv

Your son shows you a Tik Tok clip;

You both play Russian computer games.

Simulators that glorify World War Two/

mid-century armour & the cold war era

where each new development increased

penetration; rounds that defeated steel’s

stubborn thickness. You watch your son

take to the skies over maps of Ukraine.

1941. Get shot down a lot. The next best

thing to flying solo. Through his phone’s

cracked canopy he plays you a black streak

over Kyiv; a medieval, barbed arrowhead

punching through the sky’s grey cuirass. For

fifty years the fulcrum has been idle; three up

-grades, engines, radar, missiles, but never seen

combat. Seventies bones good enough to mix

it over the capital with its modern successors,

flankers & frogfeet; a retro jet where the ghost

got good purchase from his re-engineered multi-

role fighter. The first ace in a day in fifty years.

Not since Alam’s F-86 sabre rattled in the Indo-

Pakistani war has the aerial world revelled in six

kills in one day. Your son doesn’t bother to fact

check the video, sold on social media’s bravado;

a pilot’s last stand. He tells you the ghost was shot

down, but ejected. His short clip trimmed to fit.

READ MORE…

Contributor:- B. R. Dionysius

; Place: - Ukraine

; Writer: - B. R. Dionysius

; Tags: - machinery

, - Poetry

, - social commentary

, - social media

, - voyeurism

, - War