From October 1st to the 8th, the Mexican Cultural Institute of New York paid tribute to the centennial of Octavio Paz’s birth with a series of discussions, readings, concerts, and film screenings. A prolific poet, essayist, intellectual, translator, editor, publisher, and diplomat, Paz published his first poetry collection, Luna Silvestre (Wild Moon, 1933) at 19 years old, penning over 26 volumes of poetry until his death in 1998. Paz was also an accomplished essayist: his 1950 treatise on Mexican identity, El laberinto de la soledad (The Labyrinth of Solitude) is considered a seminal work of literature. The recipient of the Cervantes award in 1981, the American Neustadt Prize in 1982, and the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1990, Paz founded three literary magazines, Taller, Plural, and Vuelta; Vuelta is still published as Letras Libres.

Now that we’ve gotten that dry but necessary introduction out of the way, let me truly begin.

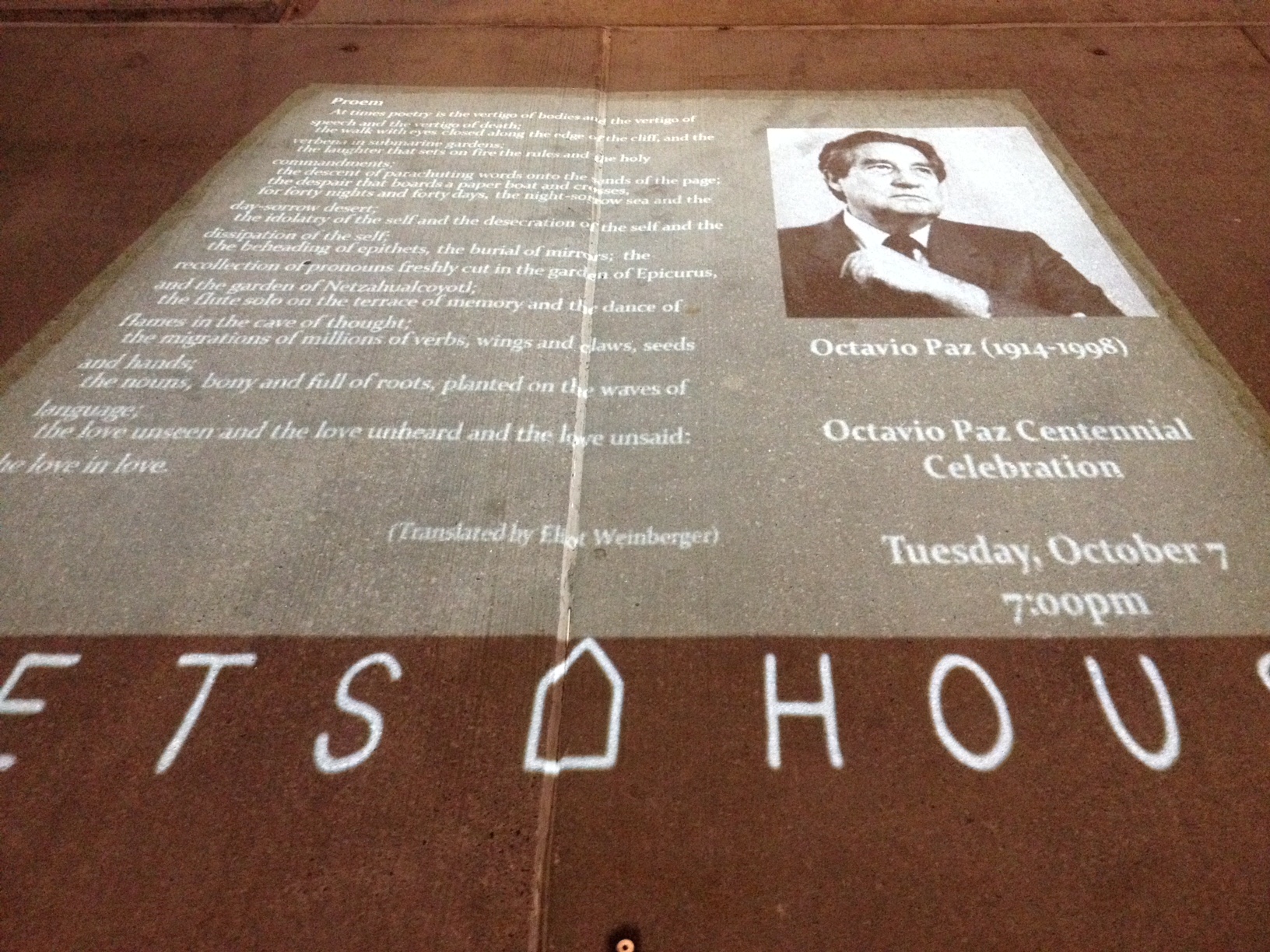

The centennial celebration was a sumptuous banquet I wanted to gorge myself on until I developed gout, like those rich men of old. I eagerly chased Paz throughout New York City, from the second-floor gallery of the Mexican Consulate in Midtown to the ornate ballroom of the Americas Society in the Upper East Side, and finally to where the river meets the city, the “navel of the poetic universe,” as Paz’s translator Eliot Weinberger playfully referred to the Poets House in TriBeCa.