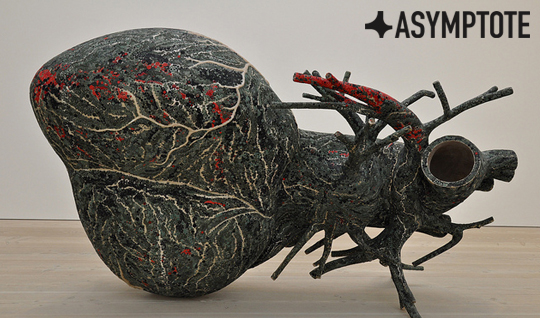

The legacy of Romanian surrealist poet Ghérasim Luca is his singular style: ferocious in desire, elaborate in theory, and fraught with the contradictions and impossibilities of translating human emotion into language. In the following essay, Jared Fagen situates Luca in his rightful place within the Surrealist canon in a comprehensive and discerning study of his love poem, La Fin du monde: Prendre corps.

The heart has its reasons of which reason knows nothing.

—Pascal

Ghérasim Luca’s La Fin du monde: Prendre corps (The End of the World: To Embody) deserves a place within any discussion of the surrealist love poem. Indeed, in the spirit of Pierre Reverdy’s contradictory conjoining of objects (following Lautréamont’s “dissecting-table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella”), the chance amorous encounters of André Breton’s Nadja, and the startling, ambiguous juxtapositions of Robert Desnos’s Liberté ou l’amour! (Liberty or Love!), a resemblance between the French treatment of love and Luca’s own handling can be undoubtedly determined. But for all the impassioned intensity, violent eroticism, and revolutionary fervor it shares in common with the works of such surrealist masters, Luca’s poem can also rightfully be situated—like the poet himself—just outside this conversation, on the fringes, or raised perhaps after its conclusion, in the exhaustion and wake of interpretation.

A founder and member of the short-lived Romanian circle (1940–1947), with Gellu Naum, Dolfi Trost, Paul Păun, and Virgil Teodorescu, Luca and his contributions to surrealist aesthetics are distinct precisely because of the tradition from which they spring (and disrupt) and the origins they seek to restore. This subtle yet significant variation of love between Luca and the French surrealists relies primarily upon a deviation of linguistic usage: despite the spirit, a rift (or departure) can be discerned on the surface—the body—of La Fin du monde; one in which love is performed by a peculiar operation of language that is as native as it is natal, as in place as it is apart. “If I am speaking only the language I have been taught,” writes Breton in L’amour fou (Mad Love), “what will ever serve as a signal that we should listen to the voice of unreason, claiming that tomorrow will be other, that it is entirely and mysteriously separated from yesterday?” For Luca, the question is fundamental to his own poetic project, yet is itself futile: “Putting aside the precariousness of man’s existence, his rudimentary biology leaning towards the reactionary, the funereal, with the vague and progress-inducing hope that everything will be solved tomorrow, when I know that this very tomorrow will always be late in arriving, because any tendency to surpass and shatter our own limits is prohibited because of our good sense, because of our modesty and rationalism.”

These two quotes reveal an interesting disparity between an amorous poetic language in service to stifling the world of reason in order to eclipse and transform it, and an amorous poetic language whose endeavor to seek respite or refuge from the progressive world results in its anguished expression. This latter point is critical to our experience of Luca’s poem. For Breton, surrealist love offers possibility, optimism, hope: the perpetual pursuit, possession, and renewal of love’s meeting as if—like the penultimate poem in his L’air de l’eau professes—“Toujours pour la première fois” (“Always for the first time”). For Luca, love is a construct already narrativized, or “ready-made,” always despairing of the revolutionary freedom it purports yet ultimately fails to fully achieve. Like Antonin Artaud’s Van Gogh, the “I” of Luca’s La Fin du monde is suicided by society, discharging its lascivious behaviors within “the myth of reality itself,” a reality that is “terribly superior to all history, to all fable, to all divinity, to all surreality.” READ MORE…