We all love our books, but at what point does that love become reductive—or even dangerous? Italian writer Michele Mari weaves elements of materialist obsession into his fictions, describing how one’s attachment to literature can create falsifications, egomaniacal delusions, and objectifications of the people around us. In this following essay, Francesca Mancino takes a close look at Mari’s You, Bleeding Childhood and the recently published Verdigris, tracing their narratives in their manifestations of literary greed.

In the threaded lines that clutter all but the gutters of his works, Michele Mari comes close to Becca Rothfeld’s fantasy of excess, as detailed in her essay, “More Is More.” There, she writes, “I dream of a house stuffed floor to ceiling; rooms so overfull they prevent entry; too many books for the shelves; fictions brimming with facts but, more importantly, flush with form; long tomes in too many volumes; sentences that swerve on for pages; clauses like jewels strung onto necklaces. . .” In both the collection You, Bleeding Childhood (2023) and the novel Verdigris (2024), translated into English by Brian Robert Moore, there is a feeling that the text cannot contain the objects described. It is as if the words command a vaster space than a page can allow for.

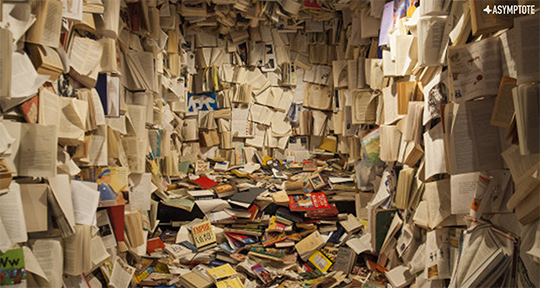

Mari’s work toes the line between the wonder and the obscenity of excess; in both You, Bleeding Childhood and Verdigris, the author presses his readers to think about its many forms and their respective limits. Reflected in his writing style, one could almost say that there is too much in Mari’s books—too many literary objects, household items, convoluted adjectives, coveted authors, and blended dialects. In Verdigris, the walls of a home have almost no free space because “everywhere has gradually been overrun by objects and signs drawn on paper, when not by symbols traced directly onto the plaster. Anyone walking into that room would have the impression of a random and compulsive clutter, as though owing to a kind of horror vacui.” The narrator, Michelino, reminds the reader that the objects are not arbitrary, since he and Felice, the house’s owner, share an intimate knowledge of “every single element” tacked onto its surfaces. READ MORE…