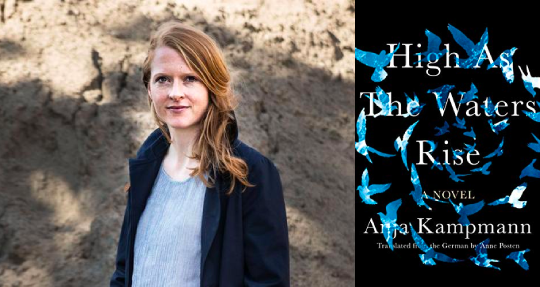

High as the Waters Rise by Anja Kampmann, translated from the German by Anne Posten, Catapult, 2020

In the rich silt into which Titusville, Pennsylvania sinks its foundations, there was only one spot where it was possible to strike oil at the extraordinarily shallow depth of sixty-nine feet. On August 27, 1859, a small group of men, at the last-ditch orders of one Edwin Laurentine Drake, sank their pipes into the ground—guided by that unknown intuition which, in retrospect, looks terribly similar to fate—and black gold flowed forth. It is how the world flows forth from a single life, from one man’s fortune to a new forever, a radically altered world.

The idea of fate, its shrouded force, is perhaps the only abiding salve for the more devastating consequences of self-awareness. We look back on our times to construct an architecture of experiences, arranging fragments by our available logic to see what structure rises from the flood—what materializes in the aftermath to become that one reference by which we can define, or justify, our lives. For some reason, we always urge towards a singular narrative, despite sharing in the overarching suspicion that the life one leads is not one, but always many. The salvaging of this steadfast, solitary lesson is a comfort—that it indeed has all been for something. Without it, there would be only darkness, that eternal torrent, that deafening collapse.

Because Anja Kampmann begins High as the Waters Rise with an ending, we arrive at the temporary space between the shock of happening and the proceedings of salvage. Waclaw and Mátyás are longtime companions working on an oil rig, sharing in a rare and profound intimacy that dissipates the customary subscriptions of male camaraderie. When Mátyás vanishes from the ship in an incident so abrupt and absurd that it seems almost mystical, Waclaw is stirred into a potent, hypnotic grief—a grief that necessitates the sea, the infinity it conjures, which Kampmann calls upon in the vignette that opens the text: “There would only be sea, piling up and up. There would be no north or south. The water would swallow even the cries of the storm, which no ear would hear.” In the midst of these tides—which overwhelm the daily rituals of work, care, and thought—is the solitary island of memories, visions in which Mátyás is frayed at the edges by recall. Only these mirages anchor Waclaw: these small footholds of before, in the vast midnight of after.