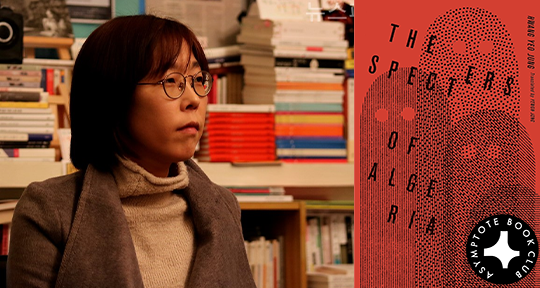

Amidst the mysterious, intricate narrative of The Specters of Algeria, there is another elusive, shrouded text: the only play that Karl Marx had ever written. This absurdist work, which gives the novel its name, goes on to inflict immense violence onto a circle of close friends, initiated by the hotheaded crackdowns of a censorious regime. In her generation-spanning, multi-threaded debut, Hwan Yeo Jung spins a fascinating inquest into authorship, aesthetics, authoritarianism, and how such things resonate into our intimate relationships. As the arrival of an exciting new voice in Korean writing, we are thrilled to introduce this fascinating inquest into political and human nature as our Book Club selection of April.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

The Specters of Algeria by Hwang Yeo Jung, tr. from the Korean by Yewon Jung, Honford Star, 2023

In her theorizing of anti-neocolonial translation, Don Mee Choi has described the experience of speaking as a twin—in the context of a Korea divided by colonial powers in twain, existing inside a language that has been colonized and recolonized by invasion and annexation, Choi describes the act of translation from between two nations that have never technically stopped being at war. This twinning across history is an idea that came to me again and again as I read The Specters of Algeria by Hwang Yeo Jung, translated by Yewon Jung. Hwang Yeo Jung’s first novel, released in Korean in 2017, takes an incredibly cerebral dive into the minds of two childhood friends who do not quite understand the circumstances of their own upbringing. In seeking answers to the dissolutions of their families and friendships, Yul and Jing (who are also Eunjo and Hyeonga, and maybe also Yeonghee and Cheosul, and maybe also Lily and Marx) sink deep into the fog of memory and a historical era, whose sins are often swept under the rug.

This labyrinthine novel bears rereading, as moments that were baffling on first readthrough settle into clarity when revisited. In the first chapter, for instance, we learn that Yul’s father, Han Jiseop, is terrified of books and paper, burning every scrap he discovers in Yul’s secret keepsake box of Jing’s letters. As a child, Yul does not understand her father’s fear. It is only later in life that Yul learns her father was once a playwright who, along with the rest of his theatre troop (including Jing’s parents), was arrested for producing “seditious materials” about communism. The resulting violence against Jiseop and his fellows ripped their friendships, and in some cases even their minds, apart. When Yul comes upon Jing’s mother Baek Soi on Jeju Island, Soi’s mind has crumbled completely, able to remember only her son and nothing else. But inside her backpack is the titular play that caused them all so much anguish—The Specters of Algeria.

This play resurfaces in Soi’s broken mind, haunting her with memories of times before the break, and pointing to one of the key concepts of this novel—the importance of naming. In her mind’s eye, Soi travels back to recitations at gatherings when Yul was a child:

“What on earth does it mean for someone to feel something about something?” Jing’s mom asked.

“Do you want to be human?” my dad asked in return.

“Tell me a secret,” she said.

“A secret about what?”

“About anything.”

“Find a contradiction.”

“If I do, will you give me a name?”

“Why do you need a name?”

“Because I need courage.”

“Then I will.”

“What is my name?”

“Hammonia.”

“And who are you?”

“Who am I?”

“Fred.”

READ MORE…