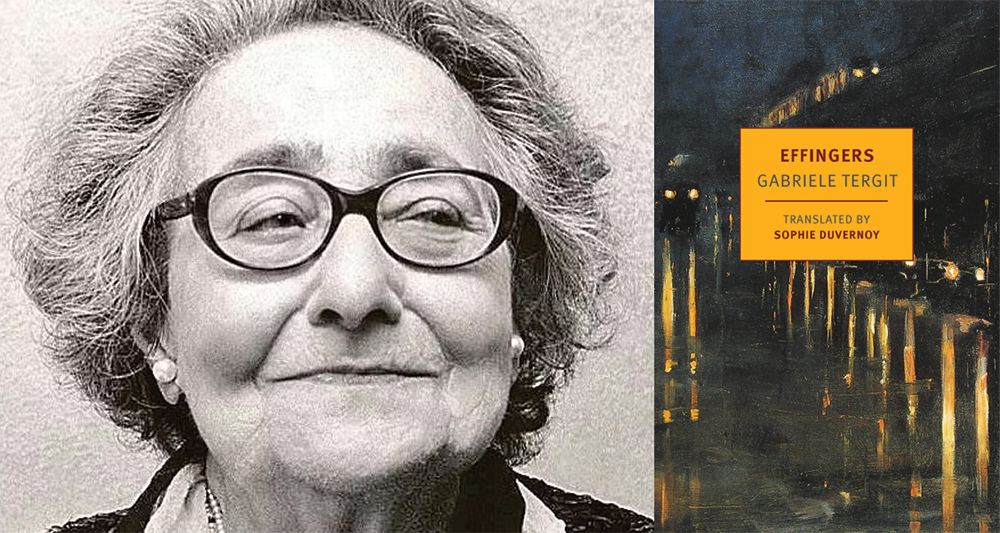

Effingers by Gabriele Tergit, translated from the German by Sophie Duvernoy, New York Review Books, 2025

There are few endings more shocking than that of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, when, after hundreds of pages of convalescence and long discussions, its hero is called down from the Swiss sanatorium to the battlefield:

Thus he lay; and thus, in high summer, the year was once more rounding out, the seventh year, though he knew it not, of his sojourn up here.

Then, like a thunder-peal—

Mann refuses to complete his sentence, specifying only that the thunder-peal “made the foundations of the earth to shake”; it is too well known what it portends. It is the Great War, and Hans Castorp must rejoin the world before he can leave it. Suddenly, from one paragraph to the next, he is in the trenches, and Mann can’t help but describe the scene. Castorp is in the mud, beneath the rain, a town on fire behind his back, the enemy before his eyes—and “What is it? Where are we? Whither has the dream snatched us? Twilight, rain, filth.” Whether he’s ill or not, the question that Mann has asked over the course of the novel, no longer matters: he’ll live or die on the battlefield.

That’s the trouble with writing a novel before history did us the courtesy of ending. Mann began The Magic Mountain in 1912, when all of Europe knew war was coming, and sat sagely at dinner tables discussing it. Two years later, that war had begun, and the world had ended. The novel Mann had begun could no longer be finished; what ought to have been the main performance could no longer be more than a happy prologue to the swelling act. The Magic Mountain was published in 1924. There was no more kaiser, there was no more tsar, there was no more Europe.

Gabriele Tergit’s Effingers was conceived in the new world, eight years later in 1932. Things were different, the great break was over, the war was long behind her, and so too were the revolutions that followed. READ MORE…