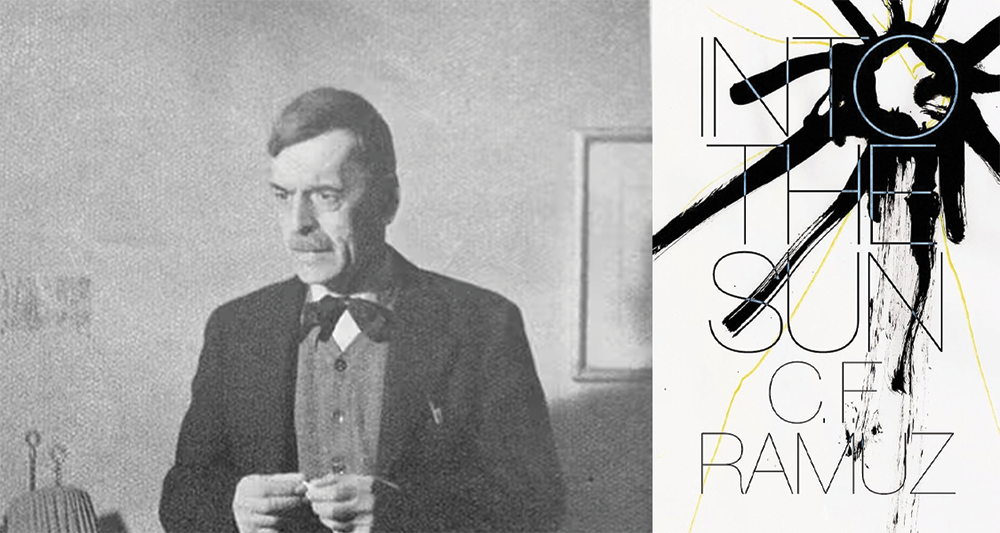

Into the Sun by C. F. Ramuz, translated from the French by Olivia Baes and Emma Ramadan, New Directions, 2025

Originally published in 1922, C. F. Ramuz’s Into the Sun is a quietly devastating depiction of the climate crisis, centring its narrative around the predicted outcome of the sun eventually engulfing the Earth. Catastrophe narratives can lean into the dramatic, but among Into the Sun’s distinctive qualities is the resistance of hyperbolic description and genre conventions; instead, Ramuz’s novel is filled with clarifying depictions of manifold human reactions—particularly silence, denial, and the stubborn persistence of everyday life. The structure of the novel, too, defies expectation, being composed of a series of vignettes that do not necessarily follow a narrative thread. Rather, the discrete elements resemble individual short stories that share the same backdrop and quiet, elliptical narrative. The result of these stylistic combinations work to create a text that feels distinctly contemporary, given the current global concern for climate change and its repercussions.

Ramuz’s discreet, almost detached tone is evident from the novel’s early chapters: ‘Because of an accident within the gravitational system, the Earth is rapidly plunging into the sun.’ In presenting the facts with a clinical eye, the arrival of the central revelation is underplayed, only previously intimated via subtle mentions of rising temperatures. As the news then spreads globally, the small lakeside town in which the novel is set (unnamed, but clearly Swiss in its cultural references) carries on as if nothing has changed. The villagers hear the warning, but they do not believe it. According to the psychologist Matthew Adams, eco-anxiety can manifest in a variety of ways, including denial, and this tension between knowledge and enforced oblivion forms the emotional core of Into the Sun: Ramuz is less concerned with the mechanics of catastrophe than with the psychological and communal refusal to accept it. READ MORE…