Many translators might agree that language is song, a kind of mouth music. Each text has a unique time signature and timbre, and when we translate voice, we have to open our ears before opening our beaks to become songbirds. And translators have a special insight into how a language’s sounds are made up of tones: pitches that help to convey meaning. A toneless voice, whether spoken, written or translated, is like a song without melody.

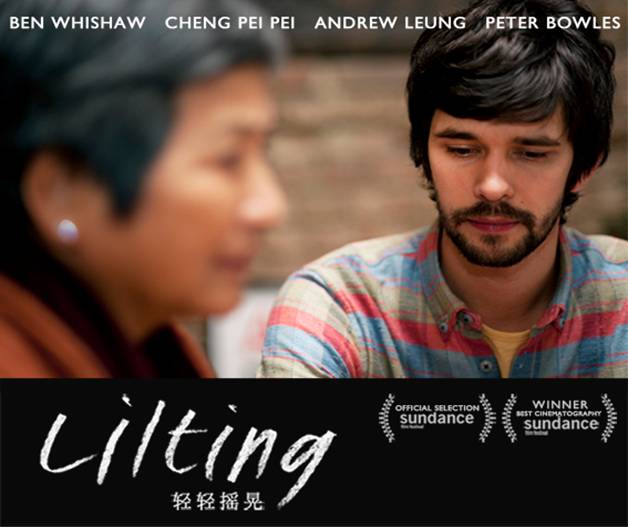

I learnt recently that mouth music is the alternative name for lilting, the subtle rise and fall of words in a sentence, and originally a style of Gaelic singing. Given that the nitty-gritty of literary translation is the picking up on nuances in voice, it strikes me as odd that translators, myself included, don’t dedicate much airtime to lilting. Why don’t we talk about lilting when we talk about voice? Isn’t it odd that translation theorists—boasting the loftiest and loveliest buzzwords in all the humanities—haven’t yet adopted it? After all, lilts are not merely ephemeral: a good prose stylist (and good translators too) can conjure them in writing. In James Joyce’s Dubliners, “The Dead” presents a good example of a lilt woven into a text, one that reverberates off the page when read aloud: