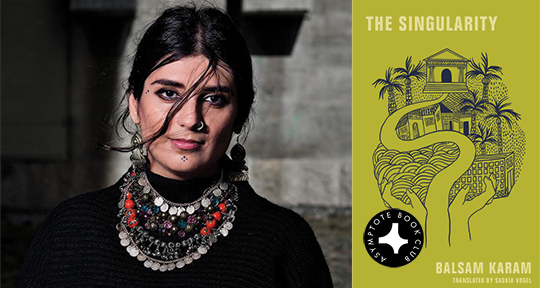

With inimitable lyricism and an impeccable sense of balance, Balsam Karam’s The Singularity addresses some of the most complex elements of contemporary social reality. Yet, even as the thrilling narrative is intricately braided with the brutal realities of loss, displacement, motherhood, and migration, the novel’s innovative structure and bold, surprising style elevates it beyond story, revealing an author who is as precise with language as she is with illustrating our mental and physical landscapes. In starting off a new year of Asymptote Book Club, we are proud to announce this work of art as our first selection of 2024.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

The Singularity by Balsam Karam, translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel, Feminist Press/Fitzcarraldo, 2024

Meanwhile elsewhere—two women perched on the precipice in a tangential encounter, spun together by forces outside their control, as if in the singularity of a black hole. One woman is about to jump off the edge, bereft after the loss of her teenage daughter; the other will frame this moment as the beginning of the end for the child in her womb. No need for spoiler alerts here: what might feature as the climax in a more conventional narrative is laid bare in The Singularity’s prologue. That it nevertheless remains absorbing to its very end is a testament to the depth of feeling and dexterity with which the Swedish-Kurdish novelist Balsam Karam orchestrates the rest of this novel about grief, loss, migration, and motherhood.

Given this jarring beginning and its atypical (or absent) narrative arc, it is perhaps no wonder that as the rest of this novel unwinds, we are met with multiple displacements in time and perspective, echoing the geographical dislocation of the two central figures—both of whom are refugees—and the all-encompassing, omnipresent nature of the trauma they experience.

Before throwing herself off a tourist-thronged cliff in a bullet-ridden city, the first woman has been searching for The Missing One: her seventeen-year-old daughter, who never came home from her cleaning job on the corniche a few months earlier. After fleeing from their home, receiving scant help from the relief organization that occasionally visits with a “hello and how are you all then here you go and we’ll be back soon, even if it’s not true,” and finding little sanctuary living in a tumble-down alleyway at the fringes of this unnamed city, the mother seems to experience the disappearance of her daughter as the final loss that makes her lose herself. “What mother doesn’t take her own life after a child disappears?” the first woman asks the universe, or “when a child dies?” the second woman asks her doctor. READ MORE…

What’s New in Translation: August 2021

New work this month from Lebanon and India!

The speed by which text travels is both a great fortune and a conundrum of our present days. As information and knowledge are transmitted in unthinkable immediacy, our capacity for receiving and comprehending worldly events is continuously challenged and reconstituted. It is, then, a great privilege to be able to sit down with a book that coherently and absorbingly sorts through the things that have happened. This month, we bring you two works that deal with the events of history with both clarity and intimacy. One a compelling, diaristic account of the devastating Beirut explosion of last year, and one a sensitive, sensual novel that delves into a woman’s life as she carries the trauma of Indian Partition. Read on to find out more.

Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse by Charif Majdalani, translated from French by Ruth Diver, Other Press, 2021

Review by Alex Tan, Assistant Editor

There’s a peculiar whiplash that comes from seeing the words “social distancing” in a newly published book, even if—as in the case of Charif Majdalani’s Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse—the reader is primed from the outset to anticipate an account of the pandemic’s devastations. For anyone to claim the discernment of hindsight feels all too premature—wrong, even, when there isn’t yet an aftermath to speak from.

But Majdalani’s testimony of disintegration, a compelling mélange of memoir and historical reckoning in Ruth Diver’s clear-eyed English translation, contains no such pretension. In the collective memory of 2020 as experienced by those in Beirut, Lebanon, the COVID-19 pandemic serves merely as stage lighting. It casts its eerie glow on the far deeper fractures within a country riven by “untrammelled liberalism” and “the endemic corruption of the ruling classes.”

Majdalani is great at conjuring an atmosphere of unease, the sense that something is about to give. And something, indeed, does; on August 4, 2020, a massive explosion of ammonium nitrate at the Port of Beirut shattered the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. A whole city collapsed, Majdalani repeatedly emphasises, in all of five seconds.

That cataclysmic event structures the diary’s chronology. Regardless of how much one knows of Lebanon’s troubled past, the succession of dates gathers an ominous velocity, hurtling toward its doomed end. Yet the text’s desultory form, delivering in poignant fragments day by elastic day, hour by ordinary hour, preserves an essential uncertainty—perhaps even a hope that the future might yet be otherwise.

Like the diary-writer, we intimate that the centre cannot hold, but cannot pinpoint exactly where or how. It is customary, in Lebanon, for things to be falling apart. Majdalani directs paranoia at opaque machinations first designated as mechanisms of “chance,” and later diagnosed as the “excessive factionalism” of a “caste of oligarchs in power.” Elsewhere, he christens them “warlords.” The two are practically synonymous in the book’s moral universe. Indeed, Beirut 2020’s lexicon frequently relies, for figures of powerlessness and governmental conspiracy, on a pantheon of supernatural beings. Soothsayers, Homeric gods, djinn, and ghosts make cameos in its metaphorical phantasmagoria. In the face of the indifferent quasi-divine, Lebanon’s lesser inhabitants can only speculate endlessly about the “shameless lies and pantomimes” produced with impunity. READ MORE…

Contributors:- Alex Tan

, - Fairuza Hanun

; Languages: - French

, - Hindi

; Places: - India

, - Lebanon

; Writers: - Charif Majdalani

, - Geetanjali Shree

; Tags: - Beirut 2020 explosion

, - diary

, - disaster

, - Indian Partition

, - motherhood

, - recovery

, - social commentary

, - trauma

, - womanhood