In addition to winning this year’s Close Approximations contest (in poetry, judged by Michael Hofmann), Swedish poet Marie Silkeberg is the author of seven books of poetry and many other works, including essays about and translations of Inger Christensen and Rosmarie Waldrop. She also works on sound compositions and makes poetry films, often in conjunction with other artists. She was born in Denmark and teaches at the University of Southern Denmark.

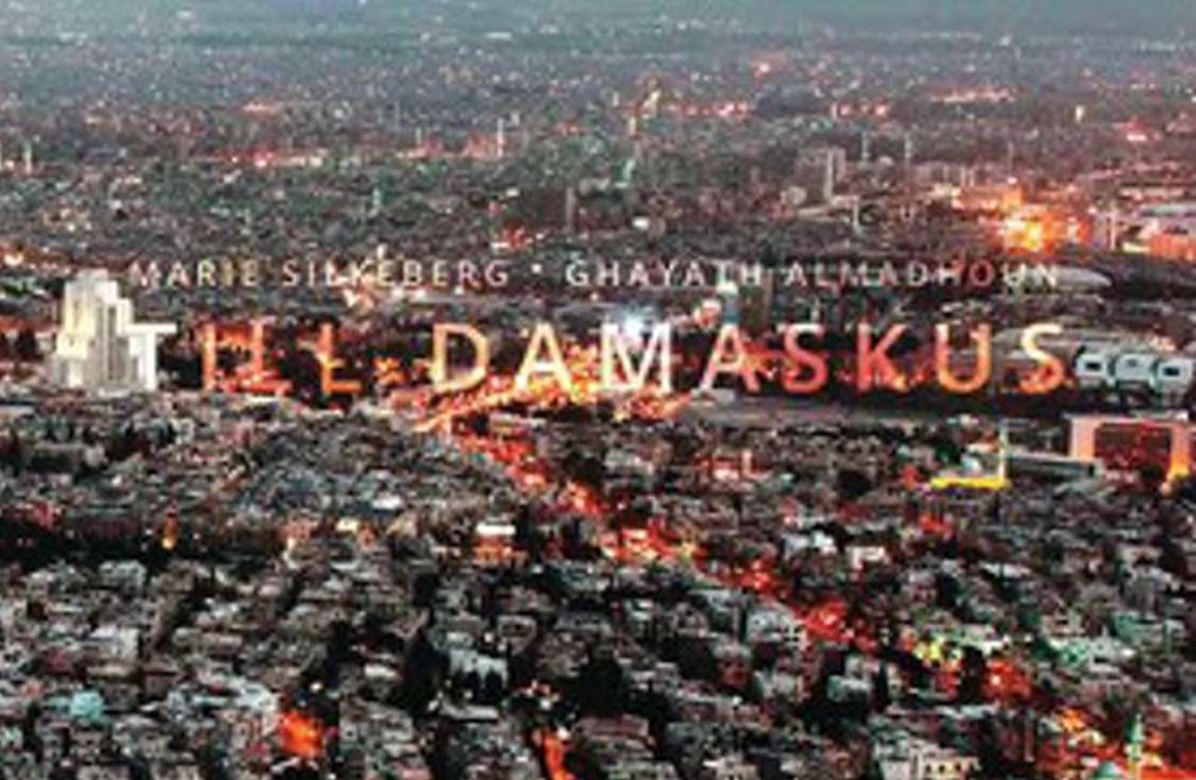

I translated eight of Marie’s poems into English while she was completing a residency in Iowa City as part of the International Writing Program in the fall of 2015. The poems form a series called “Städerna” (“The Cities”), and comprise one section of the book Till Damaskus (published in Stockholm by Albert Bonniers Förlag in 2014), a collaboration between Silkeberg and Syrian-born Palestinian poet Ghayath Almadhoun (now based in Sweden). The book explores city spaces across the world and asks questions about belonging, immigration, and identity. As we collaborated on the translations, Marie described her process and her goals for her poetry, as well as her goals for translation. In this conversation, I asked Marie to tell more about some of the initial ideas she shared with me during the translation process.

***

Kelsi Vanada: The eight poems in “Städerna” are written in what you’ve called “blocks.” They are composed by many short phrases, separated by periods, which are the only kind of punctuation that mark the poems. In addition, there is no capitalization in the Swedish poems, and many of the phrases separted by periods seem to either extend the thought of the previous phrase, or bleed into the following phrase. Why the choice of this form?

Marie Silkeberg: I’d like to revise that, actually. I want to call them “squares.” They are related to the black square of Malevich. He was a Russian painter, early 20th century. He was extreme; he made black squares on white. It is the extreme part of representation that I’m interested in. Some of the first poems I wrote were in these squares, and I didn’t know what I was doing. The space of a poem is a geometric figure for me. Or the movement in a geometric figure. These squares were invaded by a circular movement; it was a feeling of a circle inside a square. READ MORE…