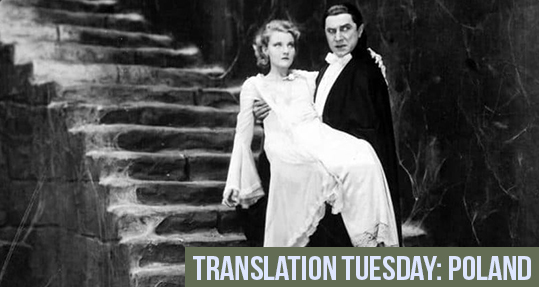

Writer, translator, and scholar Agnieszka Taborska reflects upon the literary and historical precedents of the global lockdown in these excerpts from A Woman Awaiting (The pandemic from a garret), our selection for this week’s Translation Tuesday. In coping with the trauma and uncertainty of the current pandemic, Taborska offers a bookish yet personal perspective, one informed by an expansive breadth of literary knowledge as well as familial accounts of another historical tragedy: the Nazi occupation of Poland. Paradoxically, the speaker’s isolation takes us on a necessarily cosmopolitan journey through books, recontextualizing the pandemic through the lenses of Gabriel García Márquez, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Bram Stoker, and Spalding Gray, among others. With candid, irreverent wit, Taborska chronicles her daily thoughts about the absurdities, losses, and shared anxieties of our current global crisis.

What was a day, measured for instance from the moment you sat down to your midday meal to the return of that same moment twenty-four hours later?

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain [1]

Friday, April 3

With every passing day our activities take on more of the characteristics of ritual. In the morning we top up the humidifiers on our radiators, rolling up the blinds to let the plants soak up the sun from the first minute, and wiping down with a wet cloth the leaves that haven’t had time to gather dust since we last cleaned them. For the umpteenth time we move the flowerpots around to make their residents feel as comfortable as possible. The tiles, the bathroom, the bathtub, and sink have been scrubbed raw. We recall with relief that there are still windows to be cleaned. We have shifted the furniture around, surprising ourselves with the audacity of our experimental solutions. Our new routine makes us laugh at the previous one. We strive to create hothouse conditions in our limited space. When all this is over, will we deliberately let our flat go to seed? Will we stick to a daily agenda or—on the contrary—will we turn day into night, drop in on our friends unannounced, wake up our neighbours by playing loud music at dawn, will we ditch every schedule?

The habit of checking the weather forecast is now a thing of the past. The degree of air pollution has also become irrelevant. A million dollars to anyone who, asked out of the blue, can name today’s date and day of the week without having to stop and think. On the other hand, we are getting expert at telling the hour. We have our hand on the pulse. We are aware of the days getting longer. We are familiar with the path of the rays of the sun as they move across the floor. We could tell the shadows out in the street where and how far to fall.

Our window looks out onto a small grocery store. We have noticed a pattern: young people go in wearing gloves and face masks, the old behave as if nothing was happening. Our activist neighbour picks up litter from the pavement as usual. A sight that takes me back to the past.

The dogs waiting outside the shop are surprised that their two-legged friends have suddenly been spending so much time with them. Two Labradors who came with a gentleman on a bike kill time by simulating copulation, as always. They mount each other and make rubbing motions, too brief for ‘anything’ to really happen. The infection has not impaired their erotic fantasies. READ MORE…