Though every human tragedy has its witnesses, too often those who speak the truth about them are forcefully silenced, whether by censorship, imprisonment, or murder. During the brutal Guatemalan Civil War, the violence and repression inflicted on the populace was felt heavily in the national literature, which saw many great writers suffer in its wake. In this essay, José García Escobar reports on one of the disappeared, the prolific poet Luis de Lión, and his daughter’s poignant search for her father’s lost texts.

Mayarí de León, the daughter of the Guatemalan writer, poet, and teacher Luis de Lión, was seven years old when her father was kidnapped for the first time, in June of 1973. He was kept in prison for eight days.

“When he was released, many of his friends came over,” Mayarí tells me over the phone. “We were living at my aunt’s house in Zone 1, and they came and talked to him.” She also remembers that Ana María Rodas, poet and friend of Luis’s, was there. “She cut a carnation and put it in my hair,” she says.

Mayarí doesn’t remember much else—quietness. Solemnity. Downcast eyes. She was too young and didn’t get to hear the grown-ups’ conversation, and probably wouldn’t even have been able to record more than a phrase in her memory. But she understood what was going on: men had captured her papá. Mayarí claims that from that moment on, she had nightmares. Dreams of ravines filled with dead bodies woke her in the middle of the night.

In 1973, thirteen years into the Guatemalan Civil War, the government and Guatemalan Army often targeted intellectuals and dissidents. Other writers such as Otto René Castillo and Roberto Obregón had been killed already, and many would follow, including Alaíde Foppa, Irma Flaquer, and José María López Valdizón. Then, the thirty-four-year-old Luis was an upcoming literary talent, a prime example of how Guatemalan writers, despite the lack of access to publishers or editors, continued to produce work of high quality. Luis himself, by 1973, had published two short story collections, and his novel El tiempo principia en Xibalbá had received second place in Quetzaltenango’s Juegos Florales in 1972—the first place having been declared void.

“My hands started sweating too,” Mayarí says. “Whenever I’m nervous or excited, whenever I’m taken by extreme emotion, my hands sweat. This started after my father’s first kidnapping.”

Eight days after Luis was taken into custody by the Policía Nacional, he was released. Thanks to the intervention of the Universidad de San Carlos’ student’s association, he was allowed to walk out; Luis had been kidnapped alongside the association’s general secretary. “He came out all bruised and thin,” Mayarí says. “But I know that this first detention confirmed his ideology and social calling.”

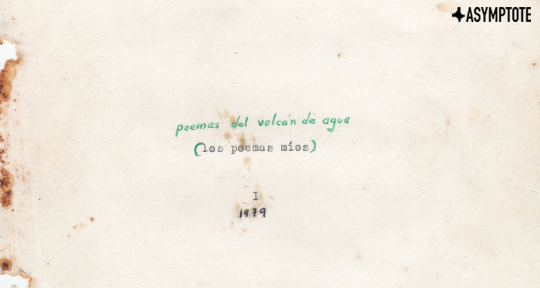

Mayarí claims that her father never told her of his days in detention, but she has come to know of Luis’s struggle through his unpublished poems and stories, collected over a search lasting for the last fifteen years. From it stems Luis’s latest publication El papel de la belleza—The Role of Beauty: an anthology of his poetry, which spans from 1972 to the very last poem he wrote before his second kidnapping in 1984. El papel de la belleza, in true de Lión style, shows many of his typical concerns and interests, his militancy and ideology, his attention to social issues and indigenous struggles, his care for the quotidian, his devastating and scenic use of language: minimalistic, casual, relaxed, always elegant. READ MORE…