José Bento Monteiro Lobato (1882-1948) is one of Brazil’s most influential writers, a prolific translator, and the founder of Brazil’s first major publishing house. His lifelike characters have become an integral part of the Brazilian society, so much so that restaurants, coffee shops, wheat flour, or readymade cake packs in Brazil are named after Dona Benta, an elderly farm owner in Lobato’s fictional works. Despite the largeness of his influence and the progressive ideas he sought to bring in Brazil through his literary endeavors, however, Lobato has been posthumously accused of racism in his literary portrayal of black people. His work, Caçadas de Pedrinho, has especially come under scrutiny for calling Aunt Nastácia as a “coal-coloured monkey,” and he continually makes reference to her “thick lips.”

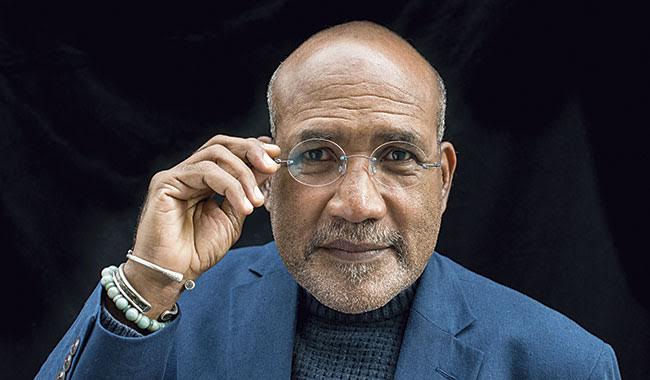

Professor John Milton’s recently launched book Um país se faz com traduções e tradutores: a importância da tradução e da adaptação na obra de Monteiro Lobato [A Country Made with Translations and Translators: The Importance of Translation and Adaptation in the Works of Monteiro Lobato] (2019) examines how Dona Benta’s character is instrumentalized by Lobato in his stories to express his criticism of the Catholic Church, the Spanish and Portuguese colonization of Latin America, and the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas, among other socio-political practices of the times. In the following interview, Professor John Milton speaks about Lobato, a household name of Brazil, stemming from his long-term research on the author’s life and works.

Shelly Bhoil (SB): Monteiro Lobato’s famously said, “um país se faz com homens e livros” (a country is made with men and books). Tell us about Brazil’s first important publishing house, which was found by Lobato, and how it mobilized readership in Brazil?

John Milton (JM): Lobato’s first publishing company was Monteiro Lobato & Cia., which he started in 1918, but it went bust from over-investment and economic problems in 1925. Then, together with partner Octalles Ferreira, he founded Companhia Editora Nacional. Both companies reached a huge public. Urupês (1918), stories about rural life in the backlands of the state of São Paulo, was enormously popular, and within two years went into six editions. Lobato quickly became the best-known contemporary author in Brazil. Dissatisfied with available works in Portuguese to read to his four children, he began writing works for children. In A Menina do Narizinho Arrebitado [The Girl with the Turned-up Nose] (1921), Lobato introduced his cast of children and dolls at the Sítio do Picapau Amarelo [Yellow Woodpecker Farm]. The first edition of Narizinho sold over fifty thousand copies, thirty thousand of which were distributed to schools in the state of São Paulo. By 1920, more than half of all the literary works published in Brazil were done so by Monteiro Lobato & Cia. And as late as 1941, a quarter of all books published in Brazil were produced by Companhia Editora Nacional.