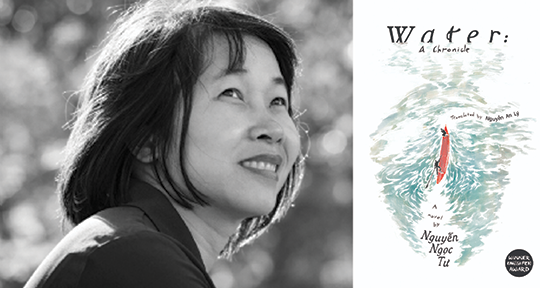

Water: A Chronicle by Nguyễn Ngọc Tư, translated from the Vietnamese by Nguyễn An Lý, Major Books, 2024

Water might have been the first floating signifier, if the image is anything to go by. Depending on its form, quantity, and culture of reception, it can be an agent of ritual purity, a destroyer of crops, a source of life, a symbol of illegible emotion. For the Vietnamese, water has been an operative metaphor and a lived reality since time immemorial; the word nước indexes both ‘water’ and ‘country,’ the two elements inseparably wedded in the linguistic psyche. A ruler of the Nguyễn dynasty once compared his precarious position on the throne to being in a boat, with the hoi polloi as the waters around him, threatening to overturn him at the slightest discontent. The scholar-translator Huỳnh Sanh Thông pointed out that Lạc, the first recorded name for the Vietnamese people, has a sonic affinity with numerous words denoting water: lạch (creek), lạt (to taste bland like water), lan (to spread like water).

The newly translated Water: A Chronicle, by the Vietnamese writer Nguyễn Ngọc Tư, embeds itself in this serpentine tradition. Better known as a litterateur of short stories than a novelist, Nguyễn Ngọc Tư’s popularity is virtually unmatched in her native country, even being named by Forbes as one of Vietnam’s most influential women in 2018. Many of her other works are similarly obsessed with the liquid element—as evidenced by their titles: Nước chảy mây trôi (Flowing Water, Drifting Cloud), Đảo (Island), Không ai qua sông (No One Crosses the River).

Though she mobilises a distinct dialect that is difficult to translate, spotlighting rural inhabitants swept up in the caprices of fate, her oeuvre is not unknown to the outside world. Her short story collection Cánh đồng bất tận (Endless Field) snagged Germany’s LiBeraturPreis in 2018, but the Anglophone sphere has thus far only received her work in dribs and drabs. This is now set to change with the groundbreaking labour of Major Books—a brand-new UK-based indie publisher dedicated to Vietnamese literature in translation, and with the poetic flair of translator Nguyễn An Lý, who deservedly won two PEN Translates awards this year. READ MORE…