In the newly ruptured world, the questions that arise all seem perplexingly novel. It is somewhat of a tonic, then, that one turns to literature to find that the queries that confound us now are more specific reiterations of questions that have plagued humanity for a long, long time. What is freedom? How do we persist through the turmoil of our nations? What does the past mean for the present? And, perhaps most pertinently, what survives? In this month’s selections in translated literature, four astounding works from around the world encounter and contend with these problems in their singular styles. Below, discover a passionate novel about a real-life Algerian bookseller, a Guadeloupe-set fiction that intermingles personal and national revolution, the latest English-language volume in Roberto Calasso’s grand series on human civilization, and a Japanese literary sensation which contends with feminine pain and perseverance.

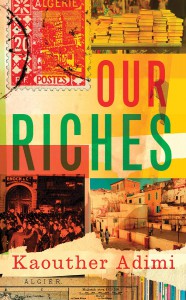

Our Riches by Kaouther Adimi, translated from the French by Chris Andrews, New Directions, 2020

Review by Clémence Lucchini, Educational Arm Assistant

Though one cannot truly stress all the qualities of Our Riches, Kaouther Adimi’s first translated novel into English by Chris Andrews, within the limits of a book review, Adimi has certainly proved that she is able to convey Edmond Charlot’s life long passion for books in less than two hundred pages. In this historical fiction, recognized with two French literary awards, Adimi finds a new way to portray her native Algeria: through Edmond Charlot’s many literary endeavors.

For those who do not know Edmond Charlot (I was among that group before reading this book), he left a great gift to the publishing world by being Camus’ first publisher, by publishing under-represented authors, and last but not least, by pioneering the design of book covers as we know it today in Western Europe, referred to as “the talk of the publishing world” in Adimi’s work. READ MORE…