On the UK tour of I Will Not Fold These Maps by Mona Kareem, translated by Sara Elkamel, Sara met with poet and translator Ali Al-Jamri to dig deep into her process rendering Mona’s work into English. They began by comparing their individual translations of the book’s opening poem, “Perdition,” and what followed was an in-depth discussion of Sara’s process and Mona’s themes as they discuss threads of loss, subversion and womanhood in the works. Both translations of “Perdition” appear at the end of this interview. Elkamel’s translation was originally published as part of her translation of Kareem’s I Will Not Fold These Maps, available in the Poetry Translation Centre’s online store and in all good bookshops!

Ali Al-Jamri (AAJ): This first part of the interview is an experiment—but let’s see if it works? I am very interested in hearing you explain your process and the granular decision-making required in translation. By way of starting this conversation, I’ve attempted my own translation of the opening poem هلاك and I’ve shared my draft with you. I find that contrasts often help us define ourselves, and so my hope is that the contrasts between our translations will clarify your process. I’m interested in any reflections you have.

Sara Elkamel (SE): I found it fascinating to go through your (beautiful) translation attempts. Usually, when I reflect on a translation of mine, I experience a sinking feeling associated with the opportunities I missed out on, as well as a sense of (dare I call it) admiration for some of the choices made—as though they were made by someone else. Looking at your translation of “Perdition” has definitely inspired those two reactions within me.

For instance, you and I have translated the third stanza very differently, and that gap helps me think through my choices. What you translated as “Another ship / short of breath / struggles on the ocean’s throat,” I rendered as “Another ship / asphyxiates / the ocean’s larynx.” I realize now that I have entirely omitted the “shortness of breath” that appears in the original. Instead, I leaned on the sound of the word “asphyxiates” to mimic that breathlessness. I’ve always thought the “x” in that word was like a noose placed in its center.

I think you and I also came to different conclusions about the body running out of breath; you interpreted it as the ship, and I as the ocean. In my reading, I felt that this poem had the tendency to give human bodies to natural phenomena; the sky has a breast, the night wears a choker of stars around its neck, and the ocean has a larynx. I realize now that the fourth stanza, “The moon spills a cloud / into the sky’s breast” was a stretch on my part. The original text does not contain the action of “spilling”—but I think I was keen on extending the poem’s tendency to set up an anthropoid actor, an action, and a subject. For better or for worse, I was trying to stay true to the poem’s intentions—or what I perceived to be the poem’s intentions—not necessarily the language itself. READ MORE…

Blog Editors’ Highlights: Winter 2025

Reviewing the manifold interpretations and curiosities in our Winter 2025 issue.

In a new issue spanning thirty-two countries and twenty languages, the array of literary offers include textual experiments, ever-novel takes on the craft of translation, and profound works that relate to the present moment in both necessary and unexpected ways. Here, our blog editors point to the works that most moved them.

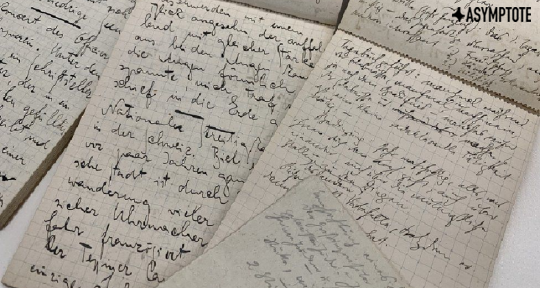

Introducing his translation of Franz Kafka’s The Trial in 2012, Breon Mitchell remarked that with every generation, there seems to be a need for a new translation of so-called classic works of literature. His iteration was radically adherent to the original manuscript of The Trial, which was diligently kept under lock and key until the mid-fifties; by then, it was discovered exactly to what extent Max Brod had rewritten and restructured the original looseleaf pages of Kafka’s original draft. It is clear from Mitchell’s note that he considers this edit, if not an offense to Kafka, an offense to the reader who has lost the opportunity to enact their own radical interpretation of the work: an interpretation that touched Mitchell so deeply, he then endeavored to recreate it for others.

In Asymptote’s Winter 2025 Issue, the (digital) pages are an array of surprising turns of phrase and intriguing structures—of literature that challenges what we believe to be literature, translations that challenge what we believe to be originality, and essays that challenge what we believe to be logic. I am always drawn to the latter: to criticism, and writing about writers. As such, this issue has been a treat.

With the hundredth anniversary of Kafka’s death just in the rearview and the hundredth anniversary of the publication of The Trial looming ever closer, the writer-turned-adjective has not escaped the interest of Asymptote contributors. Italian writer Giorgio Fontana, in Howard Curtis’s tight translation, holds a love for Kafka much like Breon Mitchell. In an excerpt from his book Kafka: A World of Truth, Fontana discusses how we, as readers, repossess the works of Kafka, molding them into something more simplistic or abstract than they are. In a convincing argument, he writes: “The defining characteristic of genius is . . . the possession of a secret that the poet has no ability to express.” READ MORE…

Contributors:- Bella Creel

, - Meghan Racklin

, - Xiao Yue Shan

; Languages: - French

, - German

, - Italian

, - Macedonian

, - Spanish

; Places: - Chile

, - France

, - Italy

, - Macedonia

, - Switzerland

, - Taiwan

, - Turkey

; Writers: - Agustín Fernández Mallo

, - Damion Searls

, - Elsa Gribinski

, - Giorgio Fontana

, - Lidija Dimkovska

, - Sedef Ecer

; Tags: - dystopian thinking

, - identity

, - interpretation

, - nationality

, - painting

, - political commentary

, - revolution

, - the Cypriot Question

, - the Macedonian Question

, - translation

, - visual art

, - Winter 2025 issue

, - world literature