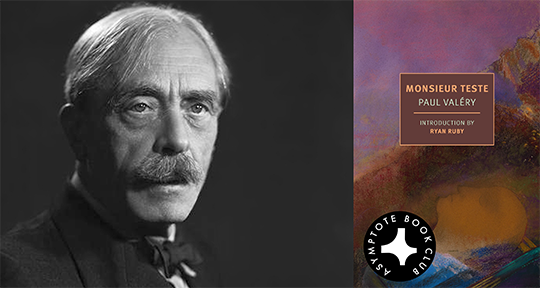

Perhaps for most of us, the idea of a poet still confers an indelible sense of the romantic, with odes and music and beautiful abstractions. For Paul Valéry, however, this association was at best weak, and at worst a diminishment of language’s complex facilities and capacity for precise worldly evaluation, never satisfying the sublimity and intensity that he sought in his writings. Thus, in 1896, he introduced an incarnation of reason and his “infinite desire for clarity” in a character named Edmond Teste, and this alter ego would remain one of the most enduring vehicles of thought throughout Valéry’s life. Now, in our December Book Club selection, Monsieur Teste, we are offered a fascinating collection of writings that track the poet’s evolving mode as he pursues his own consciousness in search of pure intellect and reason, puzzling out the dazzling relationship between language and existence. They are the imprints from a modernist icon’s search for self-knowledge.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Monsieur Teste by Paul Valéry, translated from the French by Charlotte Mandell, New York Review Books, 2024

At first approach, it’s tempting to interpret Edmond Teste, Paul Valéry’s brainchild, as an embodiment of the poet’s own curmudgeonliness, as the character’s appearance roughly coincides with Valéry’s early renunciation of poetry and recession from the public eye. In 1892, shortly after launching into the Parisian literary scene and positioning himself as Stéphane Mallarmé’s successor—as well as being in the wake of a bad breakup—Valéry seems to have had enough of the bullshit. His frustrations with literature in the afterglow of Romanticism, with writers’ delusions of grandeur and pretensions of divine inspiration, prompted a sharp pivot toward the sciences. Heavily inspired by Cartesian philosophy, Valéry came to embrace a highly empirical, mathematical approach to creation, eschewing the abstractions and vagueness he’d found so tiresome in poetry. His primary focus shifted inward, and he became chiefly interested in the mechanism behind creative construction, the series of mental operations occurring within the creator’s mind, and in testing the outer limits of human capability. In his Introduction to the Method of Leonardo da Vinci (1894), Valéry marvels at the polymath’s ability to intake external data and investigate it with the utmost rigor in order to produce works beyond our fathoming—creations so staggering that the common man, the unenlightened thinker, could only attribute them to flashes of inspiration, invocation of the Muse, or some other abstract force that Valéry so disdained. In Leonardo, Valéry found an ideal creative archetype—the “universal man”—who “begins with simple observation, and continually renews this self-fertilization from what he sees” in contrast to the lesser, unempirical thinkers who “see with their intellects much more often than with their eyes.” Valéry remarks that “when thinkers as powerful as the man whom I am contemplating through these lines discover the implicit resources of the method . . . They can, for the moment, admire the prodigious instrument that they are.” Shortly after publishing this study, Valéry continued on this theme with the first instalment of the Teste cycle, The Evening with Monsieur Teste (1896). This and the subsequent works and fragments of the cycle have now been arranged in a single volume: Monsieur Teste, a luminous new translation by Charlotte Mandell. READ MORE…