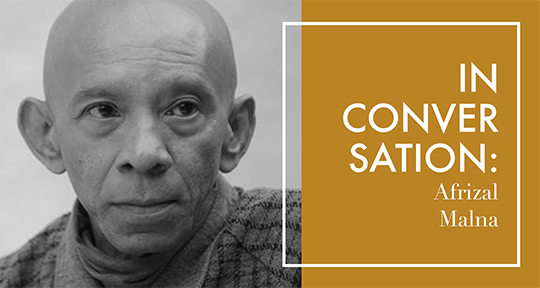

In contemporary Indonesian literature, the writer Afrizal Malna has earned his own movement. Coined by Universitas Gadjah Mada professor Faruk HT, the Afrizalian has come to mean “seemingly disjointed images and ideas wrapped inside deceivingly simple phrases,” according to University of Auckland’s Zita Reyninta Sari, who goes on to elaborate the ways that it puts “everyday objects, especially those which in a glance are the most mundane … in the spotlight.” In his foreword to Afrizal’s Anxiety Myths, translator Andy Fuller also contributes to the definition: “An Afrizalian aesthetic is an engagement with the physicality of the city. How the body collides and rubs up against the textures of the city; of the varying intense urban spaces of everyday life.”

A SEA Write award-winning writer and artist sketched as “one of Indonesia’s best contemporary poets,” Afrizal’s works have been translated from their original Indonesian into languages such as Dutch, Japanese, German, Portuguese, and English, and have received accolades from literary award-giving bodies in Indonesia and beyond. To name one, Daniel Owen’s translation of Afrizal’s poems was the winner of Asymptote’s 2019 Close Approximations Prize.

In this interview, I spoke with Afrizal—currently in Sidoarjo in East Java—with the help of Owen’s translation. Our discussion covers the Afrizalian literary movement within contemporary Indonesian poetry and drama; the terrains of linguistic hierarchies and reader reception; and his latest poetry collection Document Shredding Museum, originally published as Museum Penghancur Dokumen in 2013.

Alton Melvar M Dapanas (AMMD): Your latest collection, Document Shredding Museum, is now out from World Poetry Books. Could you tell us about the collection’s journey?

Afrizal Malna (AM): This edition of Document Shredding Museum is actually a revised, second edition of the book; the first edition was published by the Australia-based publisher Reading Sideways Press in 2019. In Indonesia, it was published a decade ago. The answer I’m giving you to this question now is probably quite different from how I would have responded back then.

This book was written between 2009 and 2013, over a decade after the fall of the Suharto regime and the 1998 Reformasi. This regime ruled from 1966 to 1998 as a result of the 1965 tragedy—the massacre of members of the Indonesia Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia or PKI) and those accused of being Communists, alongside the overthrow of the prior president Soekarno—which is still full of question marks even now. 2009 to 2013 was a time when the Indonesian people began questioning: what resulted from the 1998 Reformasi? Has there really been a fundamental change? We wondered if the powerful in Indonesia will always be prone to nepotism and its corollary effects—such as legal, ethical, and human rights violations, as well as corruption.

It was also during this time that I lived in Yogyakarta, in a Javanese cultural environment, occupying the boundary between village and city as a blurred space in Nitiprayan, Bantul (still a part of Yogyakarta). This became the moment for me to start from zero, and to allow my activities to mimic the wind, moving to find empty spaces and lowlands. This blank slate could shift the past—which was filled with hope for political change, as well as hope for literature and art to respond the 1998 Reformasi.

Global society at that time was facing social upheaval and natural disasters. When the earthquake in Padang, West Sumatra happened, I was living in a house that I had rented from a family of farmers—an old, fragile Javanese house (rumah limasan) made of wood. The earthquake made the house convulse, and it was as if the house were dancing along to the earthquake’s rhythm in order to avoid collapse. When the earthquake stopped, not a single part was damaged, but many of the houses made of stone or cement had cracked or collapsed. It felt as if the wind had vanished. Leaves were stiff like in a painting, and the feeling of solitude, of quiet, was stifling.

That natural disaster, among many others, reflected the awareness that our bodies and our technology were paralyzed, powerless. Our ancestors, who had a long history of facing disasters, may have known how to read the portents of an upcoming disaster as an ancient form of mitigation, but this knowledge was not passed down to us. READ MORE…