This month, our selection of noteworthy titles include a collection of revolutionary Hindi poetry, an erotic thriller from an extraordinary Chilean modernist, an incisive novel concerning the disabled body in contemporary Japan, an intimate socio-philosophical contemplation of a loved one’s life and death by one of France’s foremost intellectuals, and more.

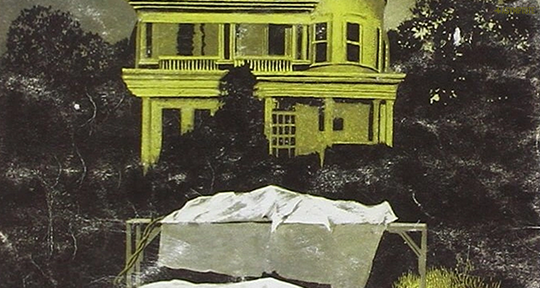

The Unworthy by Agustina Bazterrica, translated from the Spanish by Sarah Moses, Scribner, 2025

Review by Xiao Yue Shan

There’s something seductive about the nightmare, perhaps because fear is the most vivifying sensation, perhaps because beauty and horror are so finely intertwined. In Agustina Bazterrica’s The Unworthy, the night-terror has never looked so exquisite, so shimmering. With an eye for the luminous and ear for the otherworldly, familiar gothic tropes are here relieved from their muted gloom; a chimeric language sings the shadows awake, and in this chorus even the most basic signifiers of darkness regain their fearsomeness, mysticism, sensual enthrallment. The cockroach has a gleam, a crunch; a derelict cathedral is as diaphanous as a dragonfly’s wing. There are the recognisable plot-pieces—violent sacraments, echoing halls, and a wasted world—but those who command fear’s aesthetic know that the most disturbing capacity of pain and transgression lies not in their repellence, but their strange and unpronounceable allure. It is not the torturous that Bazterrica is adept at bringing to life, but the smile that slowly creeps across the face of the tortured, when they are somewhere we can no longer reach.

The Unworthy is a post-apocalyptic convent story, wherein the only known patch of livable land is occupied by the House of the Sacred Sisterhood, a cult that is at once spiritually vacuous and deeply devotional, with its faith reserved more for the House’s singular rites, rituals, and rules than any principle or entity. As is the standard for any secluded sect that positions oblivion as the only alternative to obeyance, the Sisterhood’s hierarchy is strict and immovable, the leaders are mysterious and merciless, the eroticism is violent, the violence is erotic, and the practices are senseless but methodical. The founder and head of the House is a man, but in the name of Sisterhood, all his acolytes are woman: some are servants, some are the Unworthy, some are Chosen, some are Enlightened—and only this latter group is given contact with the one known only as He. One guess as to what that means. Our nameless narrator wants to rise through the ranks, but stubborn fragments of selfhood prevent her from completely assimilating into the Sisterhood’s processions. She still has memories, desires—though they are but frayed remains. READ MORE…