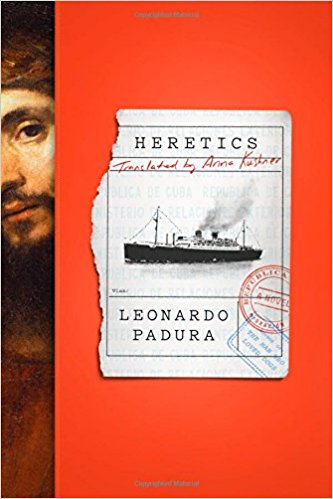

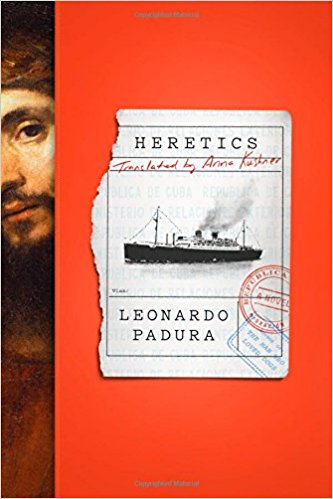

Heretics by Leonardo Padura, tr. by Anna Kushner, FSG

Review: Layla Benitez-James, Podcast Editor

Leonardo Padura’s novel, Heretics, has finally made its way to North American shores and English speakers everywhere thanks to translator Anna Kushner’s work for Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Originally published by Tusquets Editores of Spain as Herejes in 2013, Heretics is a startlingly, and in many ways disturbingly, relevant work for 2017—as rising levels of xenophobia and nationalism are straining already tense relationships across many borders and affecting refugees throughout Europe and North America. Padura’s novel opens in the Havana of 1939 with the rejection of the St. Louis, a German transatlantic liner sailing from Hamburg whose 937 almost entirely Jewish passengers were fleeing the Third Reich. Their tragic return to Europe—a effective death sentence—is watched by Daniel Kaminsky, the first character introduced and the namesake of the first of the novel’s four sections. Daniel has high hopes in his nine-year-old heart that his parents and sister aboard the ship will make it to land.

At 525 pages, Padura has ample space to leap through an ever thickening plot as his characters become more and more entangled in a seemingly unlikely series of events. Yet the read is a quick one, driven forward by drastic jumps between Havana and Amsterdam and a narrative structure which throws the reader several curveballs in the pages where a more traditional detective story might feel the need for resolution. It’s especially relentless in its final two dozen pages. This book, addicting in and of itself, will also compel readers to dive into the real history of the events on which it centers; they are oftentimes much stranger than any fiction could hope to be, even though Padura tells us right before we embark that “history, reality, and novels run on different engines.” However, to describe the work as a historic thriller, or even to focus on the mystery of a stolen Rembrandt that is woven throughout the larger plot, only hits at one level of Padura’s game. He lets us fall through history almost effortlessly, revealing the inevitable repetition of human cruelty from biblical times through the 17th century, the 20th and up through our own muddy 21st. He neither sugar coats nor exploits these horrors, to his credit.

While the novel takes one of Padura’s recurring characters, Mario Conde, as its hero, a reader uninitiated into this Cubano’s world will have no trouble becoming quickly acquainted. His prose style is elliptical; events and ideas are repeated by different characters as if Padura holds each piece of plot up to the light like a precious stone, turning it this way and that to appreciate its different angles and facets. Though Salinger undoubtedly receives the most attention, influences from Chandler, Hemmingway, Murakami, Kundera, and the occasional phrases from Voltaire’s Candide, which perhaps even inspired the name of Conde’s most pious friend, Candito, also find their place. Readers will note quite a bit of Nietzsche, too, as our hero is forced to try and make sense of the emo subculture springing up on the Island, not to mention a healthy dose of Blade Runner and Nirvana references to even things out.

Perhaps one of the most delightful plays between reality and fiction is the one Padura plays with the genre itself. Despite some dark passages, the work is deeply humorous and self-reflective, especially in the periodic wish of our narrator to compose his own hard-boiled thriller as he continually feels trapped in one himself. No stranger to taking on huge historical figures (from Adiós Hemmingway to The Man Who Loved Dogs, which stars Leon Trotsky), Padura’s Rembrant is compelling and once again does that work of blurring fact and fiction that inspires a desire for the work to have come wholly from the real world.

READ MORE…