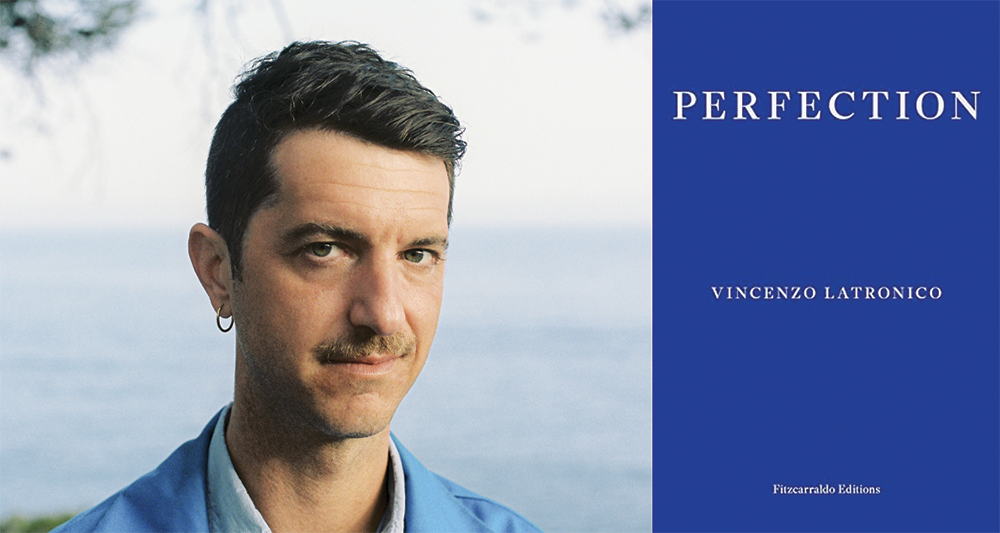

Perfection by Vincenzo Latronico, translated from the Italian by Sophie Hughes, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2025

In the early 2010s, a specific gastronomic corner of the internet flourished alongside the rise of the Instagram aesthetic; food blogging evolved beyond sites run by home cooks from around the world, and social media brought its democratization to full swing. I too was among the converted. My weekends throughout grad school became increasingly spent wandering supermarket aisles in search of capers, plum sauce, sumac, fig jam, and macadamia nuts—which were especially hard to find in India at the time—while around me, artisanal coffee shops serving cold brews were just starting to appear, and the profession of pastry chef was becoming a lucrative pursuit. At the same time, a new generation of photographers emerged in Berlin’s culinary scene, sharing dreamy images of mid-century tables with pastel ceramic bowls of oatmeal and ruby-red berry coulis, positioned in wildflower fields with Photoshopped late-evening glow. Food, like everything else in life, became a highly publicized mode to exhibit the paragons of life, beauty, and self.

Vincenzo Latronico, a Milanese author originally from Rome, has previously written four books, but the Booker International-nominated Perfection is his first to be translated into English. Though the novel is affecting on several levels, it’s important to note that it will resonate differently with readers of various age groups. As a millennial, reading Perfection was like stepping into the looking glass; at times, it felt like the narrator’s striking delineation of the digitally idealized lifestyle, tinged with biting wit, was aimed directly at me. READ MORE…