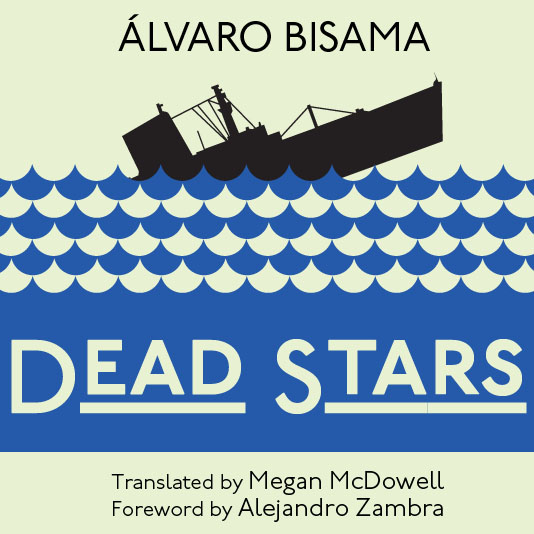

Forthcoming from Ox and Pigeon Press is Megan McDowell’s English translation of Álvaro Bisama’s Dead Stars, which won the 2011 Santiago Municipal Prize for Literature and the 2011 Premio Academia, given out by the Chilean Academy of Language for the best book of 2010.

Álvaro Bisama’s award-winning novel Dead Stars is a story-within-a-story set against the backdrop of Chile’s transition to democracy after decades under the Pinochet dictatorship, filled with characters desperately searching for a way to escape their past, their present, their future: a small-town metalhead; left-wing revolutionaries without a new cause; a brotherhood of cough syrup addicts; punks, prostitutes, and thieves. Through them, Bisama’s tragic novel explores how our choices, the people we know, the places we pass through, and the events of our lives exert an unsuspected influence long after their light has gone out and they have faded from our memory (Ox and Pigeon).

***

Javiera failed almost all of her classes. We always used to put her name on our assignments. That way she’d come closer to passing her courses. I made that gesture, same as Donoso, and Luisa, our classmate who was going out with Charly Alberti, the drummer from Soda Stereo.

You’re fucking with me, I said.

Seriously, that’s what she said, that she was Charly Alberti’s girlfriend, that he was crazy about her and sometimes he’d sneak away to Chile in secret to see her. Donoso and I knew about it. No one else. Not even Javiera, unless Donoso told her. But I don’t think he did. Donoso was very discreet. But that’s what Luisa told us. She confessed one time when she was drunk, and it was all downhill from there. She was always telling us the gory details about her and Alberti. She told us they’d spent the weekend in Reñaca, because he’d flown in on his private jet to show her his new album. She told us her parents knew about it. That it had been hard to convince her father, who was a cop and an evangelical, but Alberti had done it. That he was serious about their relationship. That he had been respectful of her. That she was still almost a virgin. I don’t know what she meant by that almost, but Donoso would hug her and sometimes she’d open her backpack and take out a giant album full of photos of Charly Alberti, a heavy book full of concert memorabilia, posters from TV Grama and VEA, and newspaper clippings. There was only one photo of them together, Alberti and Luisa, taken in the hallway of a hotel.

**

Her: Aside from many other things, the past is that: a photo taken in a hotel we wish was our home—false photographs, proof of the life we never had.

**

She said: But it doesn’t matter. The photo isn’t important. What’s important is Luisa’s role in all this, because I was with her when I saw Javiera and Donoso’s relationship start to go to shit. Because, even though she was a facha right-wing conservative, she went with me to a party thrown by the Youth League in a typographical union off Calle Colón. I don’t know why we went. Maybe we just wanted to relax. Or maybe it was easier to go there than home after classes. I don’t know. The fact is, we went. We killed time browsing thrift stores, and then we made ourselves up in the bathroom of a diner. Javiera and Donoso were at the party. We hadn’t seen much of them that semester. Javiera was in the middle of an appeal, trying to get them to let her take a class for the third time, and Donoso was busy at the restaurant. So, I went with Luisa to the party. She complained because they weren’t playing “Luna Roja,” and she insisted that Alberti was coming to see her that weekend. That she wasn’t going to drink too much because Alberti hated it when she drank, he detested drugs and alcohol. Of course, the party was full. I was drinking beer. I didn’t see Javiera anywhere. In the throng of people, I saw Donoso with a bottle of pisco in his hand. There were a few bands that played Andean music, and a couple Pablo Milanés clones. In between the bands, people danced. The party was fun, if you like that kind of thing. I didn’t really like it, but it wasn’t terrible. This was just before the mayoral election in Valparaíso. Back then, before the Spiniak case, that fat guy Pino was way ahead. At the university, someone said Javiera was going to run for council. I don’t know if it was just a rumor. It was probably true. The party would put any university leader up for election; they’d send whoever it was to campaign in villages out in the middle of nowhere, like Catemu or Puchuncaví. To us it seemed like an obvious thing that Javiera would be a candidate. So that’s how things were at that party: Luisa talking about Charly Alberti, Donoso drinking alone, Javiera nowhere to be found. The last thing I saw before disaster struck was this: Donoso sitting in a plastic chair clutching a bottle of straight pisco. That was the cut-off point, maybe. That was the moment when I lost sight of them, because Luisa went to the bathroom and she didn’t come back, and after a while someone told me: Your friend is in the bathroom crying. I went to find her. The bathroom was disgusting, but there was Luisa, sitting on the wet floor, hysterical. She had a piece of paper in her hand. A newspaper page. Luisa was holding a page from a newspaper or a magazine and sobbing hysterically. No, the fucker can’t do this to me, he can’t do this, Luisa said. I hugged her and she repeated it, he can’t fuck me over like this, he can’t do this to me, the motherfucker, she was saying, sniffling. I hugged her and she was pretty drunk and then I saw that page in her hand. There was Charly Alberti with his bride, a model. That’s why Luisa was crying. Because of that page she found on the floor of the bathroom or in the hallway. A social page, a page with the kind of short articles that close every edition of a paper. That loose page, lost at the party, a little bit of trash just like the one you have in your hands now, the newspaper page that shows Javiera with white hair. It’s like someone let these articles loose in the wind, waiting for someone else to see them and break down, just like I’m doing now, man, just like Luisa broke down then.

**

The past is always a newspaper page left behind on the ground, she said.

**

She said: But then something happened. While I was hugging Luisa, we heard noises coming from the men’s bathroom. Shouts. We heard something break. A mirror. A woman’s voice screeching: Let him go, you asshole, let him go! Then more voices. Let him go, man, you’re going to kill him. Let him go. Luisa stopped crying. I got up from the floor. There was a cumbia song playing. We walked out of the women’s bathroom. The door to the men’s room was across the hall. The paper with the photo of Charly Alberti’s wedding stayed behind on the floor. At that moment, several guys shoved Donoso out of the bathroom. He fought back, legs kicking. His shirt was torn. They threw him to the ground in the middle of the dance floor. They kicked him. We watched as they carried him to the door and threw him down the stairs. The cumbia never stopped. And then they finally played Soda Stereo. It all lasted one minute, two minutes, she said. It lasted for half of one song. We couldn’t do anything, say anything. Then, Javiera came running out of the bathroom. She went after Donoso. She didn’t see us. We stood there, paralyzed. Then, the same guys who had kicked Donoso out went back to the bathroom and hauled out a guy, unconscious, his face covered in blood; it seemed like he was someone important. I’d seen him around campus. He was always surrounded by members of the Youth League, and he always sat in front at the events they held in the quad. He never spoke. The others conferred with him in whispers. But now the same people who whispered to him were carrying him like a sack of potatoes. His mouth was destroyed. I think he was missing teeth. I guess those teeth were scattered around the bathroom and covered in urine, dirty water, and blood, she said. And the guy wasn’t responding. I guess they put him in a taxi and took him to the hospital. Luisa didn’t say anything. I remember the two of us just stood there outside that bathroom, staring at the tiles. More than the blood or the guy’s face, I remember those tiles, just that: the dragons drawn in black and white on the floor. Those tiles were worn out, chipped by the passage of time, cracked. The bathroom at my house had similar ones. I dreamed about those dragons for a week. Finally I said: What just happened? I don’t know, Luisa answered.

**

But I know. What happened was that everything went to shit, she said.

I said: It’s a law of nature. When everything goes to shit, someone’s teeth wind up on a bathroom floor. There’s no turning back. No turning back.

***

Álvaro Bisama (Valparaíso, Chile, 1975) is a writer, cultural critic, and professor. In 2007, he was selected as one of thirty-nine best Latin American authors under the age of thirty-nine at the Hay Festival in Bogota. Estrellas muertas (Dead Stars), his third novel, won the 2011 Santiago Municipal Prize for Literature and the 2011 Premio Academia, given out by the Chilean Academy of Language for the best book of 2010. His most recent novel, Ruido (Noise), was published in 2013 and was a finalist for the Premio Altazor.

Megan McDowell, Asymptote managing editor, is a literary translator from Richmond, Kentucky. Her translations have appeared in Words Without Borders, Mandorla, Los Angeles Review of Books, McSweeney’s, Vice, and Granta, among others. She has translated books by Alejandro Zambra, Arturo Fontaine, Carlos Busqued, and Juan Emar. She lives in Zurich, Switzerland.