Italian novelist Elena Ferrante has been called scrittrice oscura: an “obscure writer” who never makes public appearances and uses a pen name. In 1991, when her debut novel was due to be published, in a letter to her publisher she wrote: “I do not intend to do anything for Troubling Love, anything that might involve the public engagement of me personally. I’ve already done enough for this long story: I wrote it.”

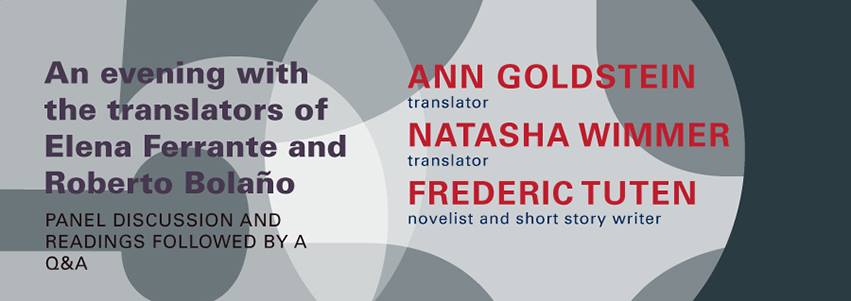

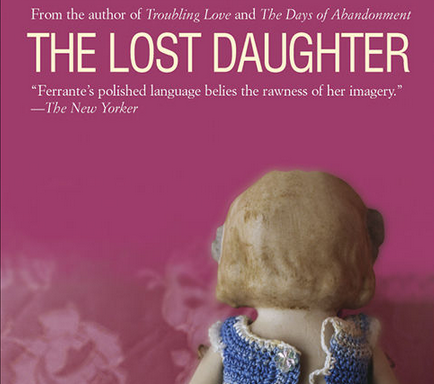

And in a recent interview, she talked to her editors about her writing practices, the female voice and the origins of her books. While the fourth and final of her Neapolitan novels, The Story of the Lost Child, published this month, is making its triumphant entrance, let’s return to La figlia oscura (2006), a precursor to the quartet, which, according to Ferrante, is the book she is “most painfully attached to.” Ann Goldstein, Ferrante’s regular translator, has chosen a nonliteral title for it, The Lost Daughter, replacing by “lost” the word that usually means “unclear” or “murky”, all the better to convey the multitude of meanings the original title encapsulates.

The “lost daughter” of the title has many incarnations: as a little girl who wanders away on a beach; as the narrator’s own daughter in a similar situation; as both of her daughters (now in their twenties), living far away and calling only when they need her; as Leda herself, who “didn’t start liking myself until I turned eighteen, when I left my family, my city.” Another interpretation of the title can be found in Nina, the mother of the girl lost on the beach, a beautiful young woman chosen by Leda as a mirror in which to scrutinize her own past life: “Choose for your companion an alien daughter. Look for her, approach her.” READ MORE…