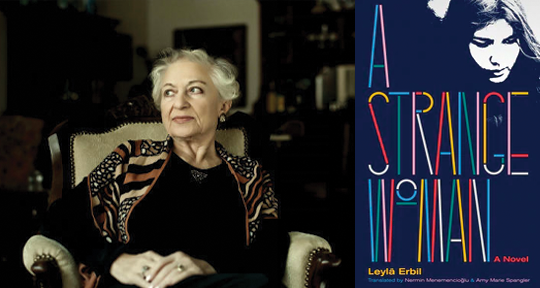

A Strange Woman by Leylâ Erbil, translated from the Turkish by Nermin Menemencioğlu and Amy Marie Spangler, Deep Vellum, 2022

Before jumping to conclusions and judgments stemming from the title of Leylâ Erbil’s debut novel, I consulted Deep Vellum’s take on the book—hoping, or perhaps wishing, that the original Turkish title would give more to go on. Tuhaf Bir Kadın, of which the English title is a direct translation, caused quite a stir in Turkey upon its publication in 1971. Since then, over half a decade has passed—a considerably long time for such a seminal and vital text to appear for the first time in English, by way of Amy Spangler and Nermin Menemencioğlu’s sinuous translation. This is also the first novel by a Turkish woman to ever be nominated for the Nobel, furthering the case for the Anglophone to take notice of this singular author, Leylâ Erbil—or as Amy Marie Spangler calls her, Leylâ Hanım.

A Strange Woman was originally translated by Nermin Menemencioğlu in the early 1970s; herself a scholar and an acclaimed translator of Turkish poetry, Menemencioğlu worked impassionedly to introduce A Strange Woman to a wider audience. However, despite receiving encouraging responses, no publisher was willing to commit. When Amy Marie Spangler stepped in almost half a century later, her contributions to the original translation further advanced the efforts towards publication—although Spangler admits in her preface that “world literature would have been all the richer” if it were published in its original form.

Further complicating the timeline is the fact that over the years, Erbil—in her signature defiance of convention—had “updated” the novel as further editions were released. Spangler worked on incorporating the new passages, only to discover that Erbil had also made additional edits and changes throughout the text. Naturally, these different versions had to be cohered, and one thing led to the other; Spangler found that “the English had been stylistically “smoothed out” in many ways.” The more she put one version against another, the more interventions she made. With both Erbil and Menemencioğlu no longer alive, Spangler and the publisher had to face and continually interrogate the ever-torturing question of how much authority the translator “could justifiably exercise.” She explains:

I decided to attach my name to the translation because the revisions were so substantial that I did not think it right to attribute it only to Menemencioğlu. I did not completely retranslate the book, but neither was the translation Menemencioğlu’s alone. My name, the publisher and I agreed, should be added so that I might bear the brunt of any criticism. I wish only that Erbil and Menemencioğlu were still with us so that we might have collaborated on the text together in real time. […] It seems to me fitting that this translation process was, like its author, rather unconventional.