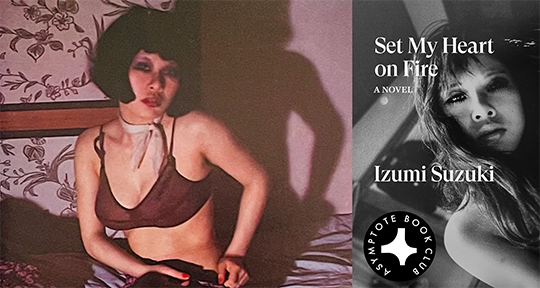

In her first novel to be published in English, the counterculture icon Izumi Suzuki draws from her real-life experiences to craft a musical, vulnerable portrait of nonconformism during a tumultuous era in Japan. From passion to nihilism, dreaminess to self-destruction, Set My Heart on Fire is unafraid of contradiction in its approach to the self, inscribing mind and body in all of its varying desire and directions. As our final Book Club selection for November, Suzuki proves to be a particularly resonant writer for contemporary readers in her audacious pursuit of pleasure and mutability in identity, all told in a vivid voice conjured by translator Helen O’Horan. In this interview, O’Horan speaks to us about how Suzuki channels a sense of disconnection, her knack for performativity, and the centrism of human relationships in her literary work.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Bella Creel (BC): How did you initially discover Izumi Suzuki’s work, and what drew you to her writing?

Helen O’Horan (HOH): I first worked on a short story for Suzuki’s collection, Terminal Boredom, just before the pandemic. I joined the project relatively late; by then, the reports had been written and the research done, so I want to credit the other translators and the publisher. That’s how I first learned about her work.

After that story, I really got into her writing—the timing was significant too. During the pandemic, I found myself feeling increasingly disconnected from my mind and body. My work as a translator wasn’t disrupted much since most of my clients are outside the United Kingdom, and it’s all online, but I started feeling like my mind and body were splitting apart.

That sense of disconnect reminded me of Suzuki’s writing—she often describes her body as something separate from her mind. Her work resonated with me at that moment, though of course, that’s just my interpretation. READ MORE…

Announcing Our September Book Club Selection: A Long Walk From Gaza by Asmaa Alatawna

Alatawan’s novel is both personal and political; at its heart, it’s a story about freedom.

In Asmaa Alatawna’s mesmerizing and clear-sighted debut novel, A Long Walk from Gaza, the long journey of migration is revealed as a dense mosaic of innumerable moments—a gathering of the many steps one takes in growing up, in fighting back, and in learning the truths about one’s own life. From the Israeli occupation to the daily violences of womanhood, Alatawna’s story links our contemporary conflicts to the perpetual challenges of human society, tracking a mind as it steels itself against judgment and oppression, walking itself towards selfhood’s independent definitions. We are proud to present this title as our Book Club selection for the month of September; as Palestine remains under assault, A Long Walk from Gaza stands as a powerful narrative that resists the dehumanizing rhetoric of war.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

A Long Walk From Gaza by Asmaa Alatawna, translated from the Arabic by Caline Nasrallah and Michelle Hartman, Interlink Publishing, 2024

There are some books that grab you from the very first line and hold your attention tight, right through every single word to the end; even once you’ve finished reading them, they keep delivering with their exquisite phrasings and stunning imagery, their deft, original storytelling. Asmaa Alatawna’s A Long Walk from Gaza, co-translated by Caline Nasrallah and Michelle Hartman, is one such novel. Through her enthralling and thoughtful prose, Alatawna unfolds idea after idea, fact after fact, emotion after emotion, recounting a tumultuous upbringing and journey that moves with both personal and universal resonance.

A Long Walk from Gaza is Alatawna’s debut in both Arabic and English—a semi-fictionalized, coming-of-age novel. Originally published in 2019 as Sura Mafquda, it explores the struggles of a teenage Gazan girl as she rebels against her surroundings, both at home and at school, and her heartbreak as she leaves Gaza for a new life in Europe. Her escape doesn’t resolve her problems but instead introduces new challenges, revealing the persistent, ongoing internal conflict of exile. While portraying life and a childhood under Israeli occupation and oppression, Alatawna also takes an incisive, knowing look at the patriarchal system of her own people. READ MORE…

Contributor:- Ibrahim Fawzy

; Language: - Arabic

; Place: - Palestine

; Writer: - Asmaa Alatawna

; Tags: - autobiographical novel

, - exile

, - feminism

, - Interlink Publishing

, - liberation

, - migration

, - occupation

, - Palestinian literature

, - social commentary

, - War

, - Women Writers