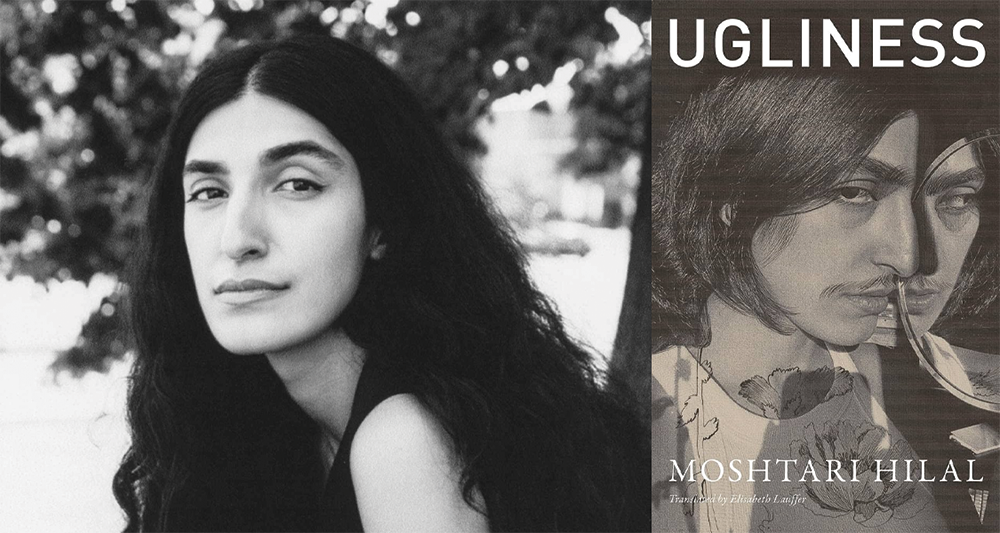

Ugliness by Moshtari Hilal, translated from the German by Elizabeth Lauffer, New Vessel Press, 2025

I have a memory. I’m about twelve years old, standing in front of a bathroom mirror, looking deeply at my body, and making a mental list of everything I could do to “improve” it. The list was ranked by struggle: the easiest came first—tasks that were beyond my control but were relatively simple (get my braces off); followed by items that would require significant effort (lose twenty pounds, maybe more). Mostly, the list lived in my head only to be recited incessantly whenever I saw myself in the mirror. Straighten curly hair. You could call them affirmations, albeit not positive ones, and always in a future tense: I will be pretty. I will be liked. Everything I hated about myself could be altered and remedied, and through this list, my body became a project.

The idea of bodies as projects is central to Moshtari Hilal’s new book, Ugliness, translated into German by Elisabeth Lauffer and published by New Vessel Press in early February. As a woman of Afghan descent now living in Berlin, Hilal examines and takes apart what she calls “the cartography of her ugliness,” an outline similar to my preteen list of remedies. “I divided my small body into enemy territories,” she writes, conducting a clinical analysis of her body and emphasizing what she considered faults. A pointed nose, an incipient mustache, a large head. The accompanying shame. However, contrary to my persistence towards the future, Hilal thoroughly stares at the past. The book begins with an all-too-common experience: childhood bullies. Looking at her school-age photos, Hilal reminisces and makes us think: Who hasn’t felt ugly at one point or the other?

Yet as the book moves forward, Hilal employs her clinical skills to take apart the concept of ugliness, leading us to its birth and attempting to understand how some of these unforgiving Western standards were created, as well as how they contribute to rejection. Sections are titled after body parts or features that can be changed, altered, modified, and reimagined to fit unattainable standards—which Hilal clarifies as being deeply entrenched in colonialism. “The notion of physical self-optimization functions as a technical extension of an ideology that upholds the necessity of shaping people into civilized modern citizens,” she writes. Blending scholarly research, sociology, history, memoir, poetry, and photography, Hilal turns her cartography (and my list) on its head, leading us down a thoughtful and compelling path. READ MORE…