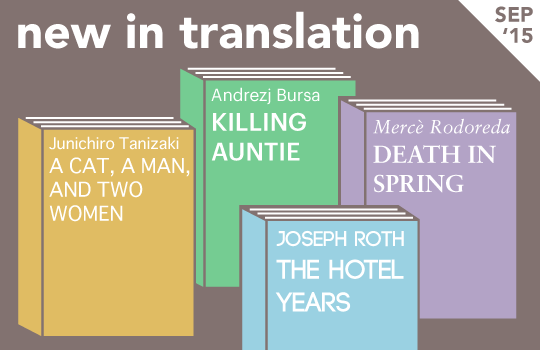

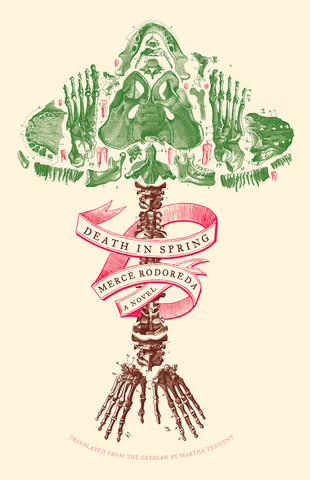

Mercè Rodoreda, Death in Spring (Open Letter, September 2015). Tr. from the Catalan by Martha Tennant—Review by Ellen Jones, Criticism Editor

Martha Tennant’s translation of Death in Spring, the (posthumously published) final novel by Mercè Rodoreda, is republished in paperback this month by Open Letter, having been long out of print. Written while in exile from Franco’s Spain during the Civil War, the novel is considered Rodoreda’s most accomplished work, and can be read as an allegory of a repressive regime.

Told through the eyes of a nameless boy who seems perpetually on the cusp of manhood, the novel recounts the cruel, bewildering traditions of a village community constantly under threat of being washed away by the river that runs underneath it. The villagers’ brutalism is bizarre and often casual—they pour cement down people’s throats as they lie dying to prevent their souls from escaping, then bury them in hollowed out trees. A thief is imprisoned in a tiny cage until he begins to behave like an animal; children are locked in cupboards until they half-suffocate; and every year a young man is forced to swim underneath the village and endure inevitable mutilation or death.